How Honey Bees Keep Their Hives Warm Given That They are Cold Blooded

Today I found out how Honey bees keep their hives warm even though they are cold blooded.

Today I found out how Honey bees keep their hives warm even though they are cold blooded.

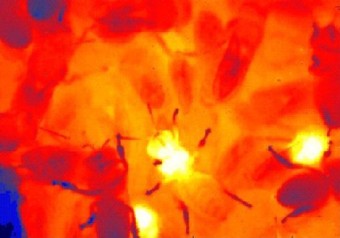

Up until only a few years ago, it was thought by many scientists that Honey bee hives were kept warm by pupae in the brood and that the bees would often congregate there to warm themselves up from the pupae. Recently, this was found not to be the case when a new Honey bee job was discovered, that of “heater bees.” Bees of almost all ages can perform this function by either vibrating their abdomens or they can also decouple their wings from their muscles, allowing them to vigorously use these muscles without actually moving their wings. This can heat their bodies up to about 111° Fahrenheit (44° C), which is about 16° F (9° C) hotter than their normal body temperature.

Another new discovery that went with this was why queen bees leave certain cells in the brood empty. It was previously thought this was an undesirable quality of a queen, so queens that left less empty cells were sought out. In fact, these empty cells are essential to a healthy hive. Before the discovery of heater bees using infrared technology, it was thought the bees that crawled in these empty cells were cleaning them out. What’s actually happening is that the heater bees will crawl inside these cells to keep the surrounding cells at the proper temperature, able to warm a maximum of about 70 or so cells per heater bee.

Another new discovery that went with this was why queen bees leave certain cells in the brood empty. It was previously thought this was an undesirable quality of a queen, so queens that left less empty cells were sought out. In fact, these empty cells are essential to a healthy hive. Before the discovery of heater bees using infrared technology, it was thought the bees that crawled in these empty cells were cleaning them out. What’s actually happening is that the heater bees will crawl inside these cells to keep the surrounding cells at the proper temperature, able to warm a maximum of about 70 or so cells per heater bee.

The heater bees can also directly regulate temperature in individual cells by standing over and pressing their thorax against a cell, something which scientists used to think was just the bees resting. In reality, they are working their wing muscles extremely hard to heat up the cell with their heightened body temperature. Why they do this has to do with job distribution.

Normally, Honey bee jobs are primarily “assigned” based on their age (see 10 Amazzzzing Honey Bee Facts for more on this). However, if the hive needs more bees that are naturally inclined towards house keeping jobs or foraging, the heater bees can adjust the temperature of certain cells to accommodate this. Raising the temperature of a cell to 95° F (35° C) rather than the normal cell temperature of about 93° F (34° C) will produce bees that are more inclined to prefer foraging jobs, over housekeeping ones, and vice-versa; so they’ll be more reluctant or more eager to change jobs than other bees their age, depending on their former cell temperature. This helps make sure that the needs of the colony can always be met given the current state of the hive and environment.

Besides performing the task of heating the brood cells, heater bees also help regulate the overall temperature of the hive. This is essential as Honey bees are cold blooded and once their body temperature drops below about 95° F (35° C), they lose the ability to fly, which is why once the outside temperature drops below around 50° F (10° C), you’ll no longer see Honey bees flying around as they’re no longer capable of keeping their body temperature high enough for flight. If the temperature drops low enough, they lose the ability to move at all.

During winter, the bees all clump together towards the middle of the hive, surrounding the queen. At this time, they allow the temperature of the hive to drop to around 81° F (27° C) on the inside of the cluster to conserve energy. Bees on the outer parts of the cluster, which will usually be around 48° F (9° C), then occasionally rotate with the bees on the more crowded inner parts, so that all the bees can keep warm enough to survive. Once the queen starts laying again, the temperature of the inner part of the hive will be raised back up to about 93° F (34° C).

In order to support the heater bees at their job, other bees are given the job of occasionally bringing food to them as the heater bee’s energy starts to run low from their constant, vigorous use of their wing muscles or “vibrating” to generate heat.

If you liked this article and the Bonus Bee Facts below, you might also like:

- Certain Ants are Used as Living Food Storage Vessels

- Caterpillars “Melt” Almost Completely in the Chrysalis Before Becoming Butterflies

- A Parasitic Wasp that Injects Its Venom Into a Cockroach’s Brain in Order to Control It

- Why Mosquito Bites Itch

- How a Firefly Glows

Bonus Facts:

- It’s estimated that about 2/3 of the honey used by a given colony is used to generate heat for the hive.

- Certain species of Honey bee will actually use this heating effect as a weapon against invading insects. For instance, when attacking wasps, they’ve been observed to surround the wasp in a ball and begin beating their wing muscles and vigorously vibrating. The combination of lack of oxygen for the wasp inside the ball and the drastically raised internal temperature will eventually kill the wasp.

- Honey bees will also use this “heat balling” technique to kill the queen when necessary, such as when the queen is no longer capable of performing her duties and a new queen is installed. This is often called “Cuddle death”.

- Most species of honey bee are thought to have originated in South East Asia. No Honey bees are known to have existed in the Americas until the Europeans introduced them to North America in 1622 in Jamestown, Virginia and it wasn’t until another 16 years that another shipment of Honey bees was sent to North America, though the existing population had already begun the process of spreading themselves in the New World. It took another two centuries or so for Honey bees to prominently propagate to the west coast of North America.

- Because Honey bees were newly introduced to the Americas, Native Americans didn’t originally have words for honey or bee’s wax and the Honey bees themselves they called “White Man’s fly”, according to the prominent 17th century Bible translator John Eliot.

- Africanized bees, a.k.a. “Killer Bees” (which aren’t nearly as deadly as Hollywood would have you believe, indeed they are popular among Brazilian bee keepers), originated in Brazil and were the result of experiments by researchers there, one of which accidentally let a Queen bee escape. From that one queen, the hives have spread north all the way to the southern United States.

- Another “killer bee” species is the Apis dorsata Honey bee. These like to build their combs in very exposed ways, like on tree branches or the like. Because of their aggressiveness, they’ve never been successfully domesticated, but many “honey hunters” (people seeking wild honey) will often harvest from their hives. However, it should be noted that the colony as a whole can be quite aggressive and when combined, are fully capable of killing a human. You’ll usually get a bit of a warning though because if you disturb them, they’ll start doing the wave, with all the worker bees thrusting their abdomens at you in time with each other, which can look like a wave or rippling effect. Continue to disturb them, and they may decide to attack.

- Bees make glue called “propolis” from various resins, tree saps, etc. they find about. They not only use it to help repair their hives, but also as a defensive weapon, particularly against insects like ants. They’ll sometimes coat branches and other things surrounding access to their hive, in order to trap any insects trying to get to the hive. In addition to that, if a predator too big for the bees to remove gets in the hive, but is subsequently killed, rather than leave the body to rot in the hive, thus compromising the health of the colony, they’ll coat it in a thick layer of propolis to mummify it.

- Another interesting job certain Honey bees have is as alarm bees. When they sense a threat to the hive, they’ll release pheromones which then cause the other bees to become aggressive and attack whatever is perceived threat.

- Honey bees have barbed stingers, unlike most other stinging bees. This results in their stinger and lower abdomen getting ripped off when they sting something fleshy like humans, ultimately leading to the death of the Honey bee. However, when stinging many other things like insects, this doesn’t happen and the bee can live to sting whatever they perceive as a threat many times.

- Virgin queens are often treated by worker bees as a worker bee until she’s mated with drones. Once she’s mated, it’s much harder to transplant her to a new hive and have her survive the ordeal. If the existing worker bees decide she’s an invader, they’ll ball her until she dies.

- Queen bees emit a distinct noise in the range of G#, known as “quacking and tooting”. When the queens are still in their queen cells, they’ll often “quack”, then once they’re out, they’ll periodically “toot”. They’ll do this most commonly when more than one queen is present in the hive, so it is thought this is some sort of way to announce themselves to any challenger. More aggressive bees, such as the queens of Africanized bees are known to more frequently do this.

- The sex of Crocodiles is determined by the average temperature of the eggs during a certain period of incubation (between 7-21 days of incubation). Specifically, if the eggs are kept above about 93°-94° F (34° C), they’ll turn into males. If the temperature is kept below 86° (30° C), they’ll turn into females. In between, it’s a mixed bag.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

This has to be the most interesting thing i learnt this week. Thanks!

A few notes: ‘The heater bees can also directly regulating temperature’ -> ‘directly regulate temperature’; ‘vice-verse’ -> ‘vice-versa’. How do the bees decouple their wings, anyways? That sounds mildly painful

P.S. How did the crocodile factoid get in there >_>

@Mushyrulez: Thanks for catching the typos. I’ll fix them momentarily. As for the crocodiles, don’t underestimate the sneakiness of the crocs.

I clear brush and mow fields with a tractor and having been attacked by ‘killer bees’ I can tell you with great assurance that if you are close enough to a swarm to see them do ‘the wave’ you are already in BIG trouble.

Don’t work in areas where you might encounter bees while wearing dark colored clothes. This is why bee keep suits are white. Generally if you see a swarm of bees less that 6 ft. off the ground the chances are good that they are killer bees. Above 6 ft. they tend to be European bees.

swarm height has nothing to do with african or european bees. and if you were attacked by killer bees, the chance you would be alive is questionable. im a beekeeper. your not.

Can anybody explain how this highly inter-dependent system developed by chance?

“…once the outside temperature drops below around 50° F (10° C), you’ll no longer see Honey bees flying around as they’re no longer capable of keeping their body temperature high enough for flight.”

Not true. My Carniolan bees occasionally take “elimination flights” when it’s as cold as 38 degrees F, and go foraging in the Spring at about 42 to 45 degrees F. One winter I cut down a Honey Locust tree in Jan when the temp was about 60 F. Feral bees covered the log ends to get the high sugar content. When the temp dropped below about 50, they left.

Re the clothing color – I work my bees in dark clothes occasionally. (Depends on what’s in the clothes drier) and have no problems because… bees can identify their beekeeper. I worked my bees wearing all sorts of colors last summer and only got stung twice – and both times it was my fault.

“No Honey bees are known to have existed in the Americas until the Europeans introduced them to North America”

Not absolutely true. Fossilized honey bees have been found in N America.

If you want to learn a LOT aout bees, go to the University of Minn’s web site. They have one of the premier bee research labs there. And if you go to the bee “Freebees” page you can find a lot of up to date posters and information.

You don’t cite any sources for the notion that changing the temperature of brood in the cells helps determine a predilection for different duties in and out of the hive. Where did you come across this bit of information?

Looks like the last paragraph in this article was included accidentally as Crocodiles are pretty distant cousins to any sort of bee. Though a swarm of flying crocodiles surely has the same lethality of a killer be swarm. Of course as I write this I haven’t slept in the past 36 hours so I might be off…

Just correct it if I am correct I don’t mean to call out the author but my mind popped a clutch shifting gears there… Almost in a Monty Python’s Flying Circus ” And now for something completely different” tradition.

@Andrew: “And now for something completely different” is our middle name.

So Mister “today-I-stole-stuff-from-the-internet”,

posting pictures that don’t belong to you is a pretty bad idea (it’s a crime actually). The right to the thermal imaging picture belongs to me (check out the homepage you copy-pasted from and you will recognize the name) – so you can either take the picture from our page OR at least give credit to the people that took it.

Sincerely

Dr. Rebecca Basile-Warner

@Dr. Rebecca Basile-Warner: My apologies. The image was pulled from http://www.bienenforschung.biozentrum.uni-wuerzburg.de/die_beegroup/research_projects/sociophysiology/ with credit in the references section, though that link appears to be dead now. What page are you referring? I’d be happy to link back to it.

That homepage isn’t active anymore but the picture is used at as well http://apiculture-nyon.blogspot.de/2012_10_01_archive.html

For the other questions:

JimQ – the phenomenon is called called “emergence”

https://www.uni-bielefeld.de/%28en%29/ZIF/AG/2007/01-24-Greve-Programm.html

Tyson Kaiser – check out Fiola Bock Dissertation or Sebstian Streits Dissertation on OPUS Würzburg it’s a pdf file – it’s in german but the summary is in english

Using a copyrighted image for means of nonprofit educational reporting (as is the nature of this article) falls under fair use, which makes it legal. Sorry, lady.

________________

the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such

use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means

specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news

reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use),

scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular

case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—the

purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a

commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality

of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Source: 17 USC Section 107 of the Coryright Act

http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#107

Rules are rules and any fool cans see by the dawn’s eerie lite that ‘does eat oats and goats eat oats and little lambs eat ivy! Put witch craft aside lets be prepared to do business as God. In God we Trust and pass off nonredeemable Federal Reserve Notes; not, understanding they are Bills of Exchange underwritten at the request of the ‘subrogated’ International Monetary Funds’ FDIC.

Truth in Lending Act Regulation Z $ are not dollars. They are ‘bills of exchange’ – INCHOATE

. . . what are you on about?

huh.. .we were reading about bees and all of sudden it changed to crocs ??? Yeah, I see the connection: eggs temperature but it was unnecessary since you didnt compare it to bees’ eggs.

Some of the stuff in this article is total b.s. Bees fly at 60degrees. Here in Canada In April my bees are gathering pollen. Flying great distances to do so. Your statement that bees lose their ability to fly at temps below 95 degrees is nonsense.

The temperature in question is their body temperature, (in Fahrenheit). They will not fly if the air temperature is below 50 degrees F. I can see your confusion.

“They’ll ball the Queen until she dies.” Of ecstasy. What a way to go.