In 1842, Ada Lovelace Wrote the World’s First Computer Program

Today I found out that Ada Lovelace was the world’s first computer programmer all the way back in the mid-1800s, writing the world’s first computer program in 1842. She was also an accomplished mathematician, which was obviously quite rare for women in the era she lived.

Today I found out that Ada Lovelace was the world’s first computer programmer all the way back in the mid-1800s, writing the world’s first computer program in 1842. She was also an accomplished mathematician, which was obviously quite rare for women in the era she lived.

Lovelace was the only legitimate daughter of Lord Byron, though she never knew him as he had left England for good in her early years and he died when she was 9 years old. Lovelace was initially taught mathematics, something which was not typical for women of the age, due to the fact that her mother was trying to drive out any insanity that may have come from Lord Byron (obviously her mother didn’t think too highly of the famed Lord). Ada showed an aptitude for math and science and one of her later tutors, the famous mathematician and logician Augustus De Morgan, noted that her exceptional skill in mathematics might someday lead her to become “an original mathematical investigator, perhaps of first-rate eminence.” How right he was.

So how did Ada Lovelace become the world’s first computer programmer when there were no computers in the 1800s? Well, there are a lot of different ways to make a computer where the way it works “under the hood”, so to speak, is very similar to modern day computers which are “Turing Complete”. If you aren’t familiar, the class of machines known as “Turing Complete”, more or less, are just machines that can produce the result of any calculation. Or, more aptly, that the machine can be used to simulate the simplest computer such that it is able to do everything this simplest computer can do. Since this theoretical simplest computer, a “Turing Machine”, can do anything the most complicated computer can do, then any machine that can do everything it can do can also perform any calculation a modern day computer can do, assuming we are ignoring memory sizes and the like (assuming infinite memory).

It turns out there was one such computer designed by Charles Babbage in the 1800s. Babbage set out to build a machine that was capable of doing a variety of mathematical calculations correctly every time, getting rid of the inherent errors that happen when humans do calculations by hand. Babbage’s earliest “computers” that he designed were not Turing Complete however. In addition to this, his computers did not run on electricity, but rather were entirely mechanical. Some of his designs ran on steam, while others needed to be hand cranked to turn the thousands of gears and parts.

Babbage’s first “Difference Engine”, as he called it, was made up of over 25,000 parts, weighing roughly fifteen tons. However, strangely it was never completed in terms of constructing the machine he had designed; it was only half built. He then came up with a second Difference Engine, which was an improvement on the uncompleted first Difference Engine, capable of returning mathematical results up to 31 digits. He never completed building this one either; though he did complete the designs for these machines that have since been proven to work. Specifically, in 1991, his second model of the Difference Engine was constructed and was demonstrated to work by doing a series of calculations. In 2000, the printer he designed that hooked up to the difference engine was constructed and was also shown to work.

So where does Ada Lovelace fit into all this? After failing to build the second difference engine, primarily due to funding problems, Babbage began designing a much more complex machine, which he called the “Analytical Engine”. The Analytical Engine, unlike his difference engines, could be programmed using punch cards, very similar to how early electrical computers were programmed (note: there is some evidence that Ada Lovelace was the one that suggested this improvement to him). This would then allow someone to make some program with the punch cards once and be able to use this program over and over again, without having to manually do everything every time they wanted to do some operation.

This machine was also able to automatically use results of previous calculations in future calculations. So you could simply put in a program, crank the gears and let the machine work, spitting out all the results of your program’s execution. This and other aspects of the underlying architecture made this machine surprisingly similar in architecture to how modern day computers work. As such, Charles Babbage is known as the “father of the computer”.

Like his early machines that were way ahead of their time, this one was simply designed, never built. Had he built it, it would have been the first machine ever to be Turing Complete. Thus, in terms of capabilities, again assuming infinite memory, his machine would have been able to do any calculation a modern day computer could do.

Like his early machines that were way ahead of their time, this one was simply designed, never built. Had he built it, it would have been the first machine ever to be Turing Complete. Thus, in terms of capabilities, again assuming infinite memory, his machine would have been able to do any calculation a modern day computer could do.

Ada Lovelace, nicknamed by Babbage “The Enchantress of Numbers”, was impressed by Babbage’s Analytical Engine design and between 1842 and 1843 she translated an article by Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea covering the engine. She then supplemented the article with notes of her own on the engine, with the notes being longer than the memoir itself. In these added notes, she included the world’s first computer program that would use the machine to calculate a sequence of Bernoulli numbers and has since been shown to be a valid algorithm that would have run correctly had the Analytical Engine ever been built.

Besides this, she also was one of the first to see that this computer Babbage designed could likely someday be used to do more than just crunch numbers, such as be used for music and other non-mathematical purposes.

Ada died a mere 9 years or so after writing this program, at the very young age of 36 years old on November 27, 1852, from uterine cancer and bloodletting by her physicians.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The First Website Ever Made

- Steve Jobs’ First Business was Selling Blue Boxes that Allowed Users to Get Free Phone Service Illegally

- How the Word “Spam” Came to Mean “Junk Message”

- Who Invented the Internet?

- The World’s First General Purpose Digital Electronic Computer

Bonus Facts:

- Half of Charles Babbage’s brain is preserved at the Hunterian Museum in London. No word on what happened to the other half.

- The programming language “Ada”, which is the “official” programming language of the United States military, was named after Ada Lovelace; the military standard for the language, “MIL-STD-1815” was given the number of the year of her birth.

- Annoyed by an “inaccuracy” in the poem “The Vision of Sin”, Charles Babbage wrote to the famed poet Alfred Tennyson requesting that he change the lines “Every moment dies a man, Every moment one is born” to “Every moment dies a man, Every moment 1 1/16 is born”.

- Ada Lovelace’s image can be seen on the Microsoft product authenticity hologram stickers.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Nice article, although the mathematical stuff makes my brain spin.

She must have been remarkable for he r time.

Incredible… it would be neat to build a smaller version of one of those machines by hand. In fact, I’ve actually talked with someone who used to write programs using punch-cards– I should talk to him about it.

Yeah, I used to write programs and check them from punch-cards. It was a g-code/m-code CNC machine back in the 80s.

This article will be in episode 17 of A Ration of Reason podcast – rationofreason.com

Thanks,

Matt

Nice article, although the mathematical stuff makes my brain spin.

She must have been remarkable for her time

Was she related to Linda Lovelace?

No Linda Lovelace’s real name was Linda Boreman

WoW, I never knew that. This lady was amazing

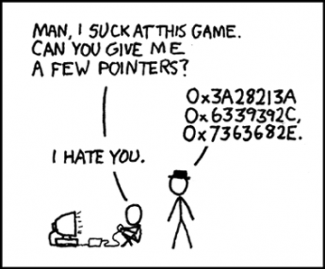

You should credit the comic to its owner

https://xkcd.com/138/

according to his license

https://xkcd.com/license.html

@Jeremy: Yep, already is in the References

Oops, I missed it. Carry on!

What was the world first computer program

??

Any proof of last mentioned bonus fact? I couldn’t find any valid source.