Why Anvils are Shaped as They Are and Why Blacksmiths Often Tap the Anvil After a Few Strikes on the Object They’re Working On

Today I found out why anvils are shaped the way they are and why blacksmith/farriers/etc. sometimes tap the anvil after a few strikes on the object they’re working on.

Today I found out why anvils are shaped the way they are and why blacksmith/farriers/etc. sometimes tap the anvil after a few strikes on the object they’re working on.

Anvil shape has evolved greatly since the earliest anvil-like objects. These primitive objects used for anvils were typically made of stone, often just a slab of rock. The first metal anvils were made of bronze, then wrought iron, and, finally, steel, which is the material of choice today for anvils, though cast iron is also used in low-end anvils (cast iron is quite brittle for this particular use and absorbs more of the hammer blow’s energy than steel does, so it is not preferred).

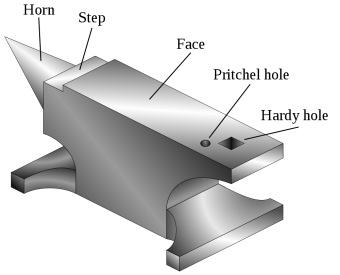

Over the centuries, the common shape of the anvil has evolved from a simple slab to the shape most of us associate with an anvil today, namely the “London Pattern”, which became common in the 1800s. While the length and overall size of the various elements can vary from anvil to anvil, the key features of the “standard” design are typically a horn, a step, a face, a hardy hole, and a pritchel hole. The primary use of these various elements is as follows:

The horn is the “front” end of the anvil which is curved. This allows the smith to hammer different curves into the piece they are working on, with the precise curve depending on how and what part of the horn they hold the piece on while they hammer it. Some anvils also come with multiple horns, of differing shapes and sizes.

The horn is the “front” end of the anvil which is curved. This allows the smith to hammer different curves into the piece they are working on, with the precise curve depending on how and what part of the horn they hold the piece on while they hammer it. Some anvils also come with multiple horns, of differing shapes and sizes.- The step is the flat area next to the horn, just below the face. This is often used as the cutting area, using the edge of the step to “cut” a piece while hammering it. However, frequent use of the step for this purpose can also damage it, so the use of tools attached to the anvil for cutting is often preferred for non-hobbyists.

- The face is the main large flat slab where most of the hammering takes place. It also contains the hardy hole and the pritchel hole. Unlike the step, it often features slightly rounded edges so that the edges don’t cut into the metal being pounded on the face.

- The hardy hole is a square hole through the anvil that allows you to secure various tools in the anvil. These tools can include chisels, various swages (used for shaping or marking the metal, generally a block of metal with a recess for forcing the metal into the shape of the recess), bickerns (smaller, specialized versions of the horn), etc. The hardy hole can also be used directly for an aid in bending or in hole punching.

- The pritchel hole is a round hole meant as an aid in punching holes through the metal you’re working on, but obviously the hardy hole can be used for this as well as mentioned. The pritchel hole can also be used for holding tools. So, basically, the pritchel hole is a round version of the hardy hole.

On a related not, if you’ve ever watched a smith work, you’ve probably noticed many of them will strike whatever they’re working on a few times, then follow it up by lightly tapping the anvil’s step or face a couple times. You may have heard that they do this to cool the hammer down by having it come in contact with the anvil, but this is the opposite of what they’d want to do. Warm hammers and warm anvils are actually what they want, because it keeps the hot metal they’re working with from cooling down as quickly, so it requires less heating while shaping, which saves time. Further, the very brief contact between the hammer and the anvil isn’t going to transfer very much heat, even if the anvil is quite cold.

In reality, they are not actually tapping the anvil for any real purpose other than to simply either rest their arm while they quickly examine the results of the last few strikes or to simply keep their rhythm while they examine the piece. In the former case, resting the hammer on the anvil next to the piece is simply a convenient place to rest it. With it in this position, it is a shorter distance to bring the hammer back up to the appropriate striking position, over say, letting one’s hammer and arm rest at one’s side while the piece is examined. In the latter case, some just find it nice to continue their hammering rhythm while they examine what they’re working on, rather than stopping completely. They only tap the anvil, rather than strike it, both to save energy and because you should never pound an anvil directly with the hammer as it can cause slight deformations to form which would then be transferred to whatever you’re working on in the future.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Superheroes Wear Their Underwear on the Outside

- Why Do Olympians Bite Their Medals?

- Why Doesn’t Wood Melt

- Why Is It Illegal to Remove Your Mattress and Pillow Tags?

- The Man Who Ate an Airplane and Three Other People Who Eat Weird Things

Bonus Facts:

- Humans aren’t the only animals on Earth that use objects as anvils. For instance, Chimpanzees often use sticks or rocks as hammers and logs or rocks as anvils in order to crack open nuts.

- Anvil firing (the practice of launching an anvil in the air with gunpowder) was once traditional in various places in the world, particularly in the Southern United States. Typically, one anvil is placed upside down with its concave base then filled with gunpowder. Another anvil is then placed on top of that anvil right-side up, so their bases match and with a fuse coming out of the inner concave area filled with gun powder. Depending on the quality of gunpowder, the amount used, and the weight of the anvil, when the gunpowder ignites, the anvil will be shot into the air to various heights. This somewhat dangerous practice was often used in substitute for fireworks at certain celebratory events. It was also once traditionally used on St. Clement’s Day (Pope Clement I is the patron saint of blacksmiths and metalworkers).

- While blacksmith is a familiar term, you may not have heard of a farrier, mentioned above. A farrier is basically a hoof care specialist that, among other things, is typically skilled at making horse shoes. At one time, most blacksmith’s were also skilled farriers and vice-verse. However, today this is usually not the case with modern farriers leaning more towards just being horse hoof care specialists and modern blacksmiths, while able to make horseshoes, usually are not skilled at also caring for horse hooves.

- The name “farrier” comes from the Middle French word “ferrier”, meaning “blacksmith”. This Middle French word in turn derives from the Latin “ferrum”, meaning “iron”.

- The name “Blacksmith” simply references the fact that they are smiths (deriving from the word “smite”, meaning “to hit”) that work on “black” metal, with the metals typically turning black from a layer of oxides after being heated. Obviously the oxide layer is generally later ground off.

- Anvils were once commonly made of wrought iron, rather than steel. Wrought iron is just iron with a very low carbon content (lower than steel or cast iron). It was once considered pure iron, but by today’s purification standards this is no longer the case.

- Steel is simply iron that has a small amount of carbon added, usually .2%-2.1% (other materials such as manganese, chromium, tungsten, etc. can also be used). The net effect of adding carbon or the like is that the iron is significantly hardened.

- When enough carbon is added (around 2.1%-4%) to the iron, rather than steel, you get cast iron, which is derived from pig iron. Cast iron is much harder than steel, but the price for this is that it is much more brittle and less ductile. The name “cast iron” comes from the fact that it has a relatively low melting point and is easy to cast.

- Pig iron is simply the result of taking iron ore and smelting it with some sort of carbon fuel, such as charcoal or coke. The name comes from the fact that the branching structure of the molds for pig iron ingots coming off a main line has the appearance of piglets suckling on a sow (an “ingot” just means a shape suitable later processing or transportation, such as a traditional gold bar type shape).

- While not up to modern standards, the earliest known steel making was done over 4000 years ago in present day Turkey. Steel pieces have also been found in East Africa from over 3400 years ago. The Chinese are known to have begun quenching their steel as recently as about 2000 years ago.

- Iron is the most common element by mass overall of any on Earth, though it is only the fourth most common element in the crust of the Earth.

- Iron is formed from decayed nickel-56. This nickel is produced in stars and is subsequently spread about via stars large enough to go supernova doing so, with it being the last element produced in those stars before they go supernova.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Here is a factoid.

“Factoid” is its own “factoid”.

Why? Because a “factoid” is NOT a “little fun fact”, but rather a “mis-fact” repeated so often as to be accepted as fact, and if ever there were a case of a “factoid”, it is the case OF factoid (so often wrongly used to mean “a little fact” that it now often means that, but isn’t).

@Tim S: pleas read this

you’re seriously basing your defense on a 20 something year old out of context bastardization of a word which was popularized by network news? rather sad. then again, so is the english language in general.

NICE FEATURE ON ANVIL. NEVER THOUGHT THERE IS SUMTHING BEHIND THE HUMBLE ANVIL TOO, TILL THIS ONE. EXCELLENT DIAG. AND LUCIDLY EXPLAINED. TNX.

Another reason to tap the anvil with the hammer is to help in quickly adjusting your grip on the hammer.

There are several good reasons for tapping the anvil. As noted earlier, adjusting grip is one. Smiths move their hands up and down the handle frequently depending on the control and force of the blow. You may start out at the end to move a lot of material when it is very hot, and then move your hand toward the head for more controlled quicker blows to work on the finish as it cools. Additionally, when you are pounding, it helps to keep a steady rhythm. By striking the anvil lightly at the same rhythm as striking the hot iron, you can keep that rhythm. A constant rhythm also help to coordinate turning and examining the piece you are working on. One of the most important reasons I use it is that when a hammer is dropped or tapped on the anvil, it bounces quite a bit. Therefore, rather than just lift the hammer like a dead weight, if you tap it, it will jump up and make it easy for the next strike. It actually jumps quite a bit, particularly considering it is 3-5 pounds of steel. A quick flick of the hand is all it takes to make it jump. Finally, of course, tapping is used to signal a striker when a blacksmith is using an assistant to work on a big piece. This is what I have noticed about tapping in over 25 years of traditional blacksmithing. I hope this was helpful.

“when you are pounding, it helps to keep a steady rhythm” Oh yes.

By striking the anvil it tells you if there is a fault in the anvil ie a crack starting

I was always told that the reason they tap the anvil was to pick up carbon from the anvil on the face of the hammer which would be imparted to the iron or steel object they were working on to make it stronger.

Highly unlikely. To impart carbon into steel, you would have to either cse harden it which only adds a microscopic layer of carbon, or remelt and make new steel from the old steel, adding carbon into the mix. A hammer will not transfer carbon to a workpiece.

The reasons for tapping the hammer on the anvil is to keep the rhythm going and to signal a partner if two people are working a piece of steel. But the main reason to tap the hammer is to make sure there is no scale (oxide) on the hammer face. The blacksmith does not want to add any scale to the hot steel and weaken it, so tapping the hammer ensures that the scale on the hammer face is knocked off.

And you sir Got it right. If there is an actual tap of the hammer after hammering it is to release slag. As for superstitions and other old fables I cannot answer. But the benefit of tapping your tool, is that any “dust dirt slag ETC” is jarred loose instead of heated/melted/pressed into your tool on the next use. If you watch a mig/flux welder as he finishes his weld, he will tap his gun nozzel on something to release any slag/dirt. Same thing.

Anvils are considered to be the oldest of tools, the ‘grandfather’. Many smiths would begin a session by making a small acknowledgement to the ‘grandfather’, a prayer, if you will. Respecting the elders of the trade, the grandfathers, the anvil. My teachers, Chris Marks & Japath Howard told me to consider that the anvil was made of glass. Don’t break the glass. In other words, don’t hit the anvil with your hammer, hit the metal that you are forging instead. Tapping lightly to keep your rhythm going as mentioned above, was ok. It was not the same as hitting.

Back when I was learning smithing from my master, he told me tapping on the anvil helped keep demons out of it.

are there any anvils that do not have a sharp point at the end their horn?

Or where the horn is removable?

There were many many shapes of anvils. And every part of an anvil can be used to shape metal. For example if you roll it on it’s side you can shape a bowl out of tin, spoons , ladles, shoulder pieces for armor, etc. Use Google to look up anvil collection and you will see some very cool anvils in all shapes and sizes.

Striking the anvil between blows is just a bad habit. Slight taps (for signaling) don’t do much damage but without something between the hammer and the anvil you leave hammer marks in the anvil. A wire brush is best for removing scale.

A harder steel plate is used for the face when an anvil is forged out of wrought iron. Tapping it with a hammer will tell you if it is separating from the base. Instead of a nice ring you will hear a thud. The separation is usually caused from the anvil getting too hot. Regardless of what anybody tells you your tools should remain cool. If not ,they will lose their temper and become as soft as the metal you are hammering.

I use a Joshua Wilkinson made in England 1860 ish. If used properly they last a long time :<0)

I was literally shown by a blacksmith, by tapping the hammer you can tell if the handle has broken or cracked by the ringtone, ping is good, thud if cracked. Try it sometime and see for yourself with any hammer. My 2 cents.

When hammering metal on an anvil the hammer face needs to be flat to the face of the anvil otherwise you will put marks into the metal. If you feel the hammer turn in your grip or notice you are making marks in the metal, a quick tap on the face of the anvil helps to re-set the hammer in your hand so that it stays flat.

The same reason,train wheels get tapped with a hammer.