The Curious Case of Giant Concrete Arrows That Stretched from New York to California

When the U.S. Post Office introduced airmail service in 1920, the mail could only be flown during daylight hours, when pilots could see where they were going. In an age before sophisticated navigation systems, flying after dark was just too dangerous. The pilots who transported the mail navigated by following roads, rivers, railroad tracks, and prominent landmarks as they made their way across the country. When these landmarks weren’t visible, they didn’t fly.

At dusk, airborne planes landed at designated airfields near railroad lines. The mail they were carrying was then loaded onto trains, which hauled it through the night until daybreak. Then the mail was loaded onto a new airplane and flown again until dark. At that rate, it took about three and a half days to get mail from New York City to San Francisco, only a day less than sending it entirely by rail, and at much greater risk and expense. If airmail service was going to survive, it was going to have to get much faster, and that meant flying at night. But how?

A SHOT IN THE DARK

On February 21, 1921, the post office launched a night-flying experiment when it sent two planes east from San Francisco, and two more west from New York. The planes were flying the first stretch in what was, in effect, a cross-country relay, much in the way that the Pony Express had operated 60 years earlier. When the pilots landed, their mail sacks were transferred to another airplane with a fresh pilot, who flew the mail to the next stop. As the planes made their way across the country, small towns along the route lit the way by keeping large bonfires burning through the night.

That was how the experimental flights were supposed to go, but that’s not exactly what happened. The westbound flights were grounded in Chicago when a snowstorm hit. And one of the eastbound flights ended when the pilot, William Lewis, crashed his plane and was killed. But the other eastbound plane made it all the way to Hazelhurst Field in New York, delivering the mail just 33 hours and 20 minutes after it left San Francisco. That’s about 65 hours faster than sending the mail by train. The very next day, Congress voted to give the Air Mail Service $1.25 million to develop the system further.

TRANSCONTINENTAL AIRWAY

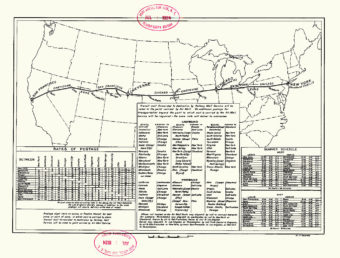

Two years later, Congress appropriated additional funds to create a lighted airway across the entire United States. From San Francisco through Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, planners devised a system of beacons and emergency runways spaced from 10 to 30 miles apart, depending on the terrain. At each location, a 50-foot-tall steel tower was erected with a rotating spotlight installed at the top.

The beacons were spaced close enough together so that when a pilot was passing over one of them, the next one would be visible in the distance. That worked in clear weather, but on a day when it was overcast and visibility was poor, the pilot might need help finding the next beacon. For that reason, the foundations for the beacon towers were poured in the shape of giant, 70-foot arrows, which pointed the direction to the next beacon. The concrete arrows were painted bright yellow to make them more visible from the sky.

LIGHTS OUT

By the late 1920s, 284 beacons had been built in a line along the 2,665-mile route from New York to San Francisco. The Transcontinental Airway System, as it was called, was a technological marvel. It worked so well that other countries imitated it. There was even talk of using light ships or anchored buoys to create routes across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

By the late 1920s, 284 beacons had been built in a line along the 2,665-mile route from New York to San Francisco. The Transcontinental Airway System, as it was called, was a technological marvel. It worked so well that other countries imitated it. There was even talk of using light ships or anchored buoys to create routes across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

But as effective as the system was, it was soon eclipsed by other advances in aviation technology. Newer planes were more reliable and flew higher, faster, and farther, eliminating the need for so many emergency runways. Radio navigation systems made it possible for pilots to follow a radio signal for hundreds of miles, even in poor visibility. That made the light beacons obsolete, and the system was dismantled in the 1940s. The towers ended up as scrap metal, which was used to build tanks and ships during World War II. In coastal areas, many of the giant concrete arrows were destroyed to prevent enemies from using them as navigation aids. But many still survive to this day, the only physical reminders of the days when pilots could fly all the way across the country by sight without getting lost in the dark.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

And to think that nowadays all we have to do is open our smartphone, write our email and hit Send! Amazing advances in less than a century.

Everyday’s a learning day haha that’s amazing! Hey El Rodgers there’s even the amazon tool that you can just speak to I can’t remember what it’s called is it Alexis? I bet that could could write and send the email for you it’s incredible

Got any Google Map links?

I wonder if these concrete keys could be the inspiration Supermans fortress of solitude key?

Well, this is all very interesting. I never knew this about the US Postal Service. Haha, typical Americans then and now; we don’t like to wait for anything. Today the same messages can be sent electronically in a fraction of the time.