How the Freedom of Information Act Came About

The Freedom of Information Act was passed in 1966—and it was the very first law in American history that gave regular citizens the legal footing to compel the government to release internal documents. Before that—not for you! Getting it passed was a long, tough battle. (And it’s still going on.) Here’s the whole story.

The Freedom of Information Act was passed in 1966—and it was the very first law in American history that gave regular citizens the legal footing to compel the government to release internal documents. Before that—not for you! Getting it passed was a long, tough battle. (And it’s still going on.) Here’s the whole story.

MR. MOSS GOES TO WASHINGTON

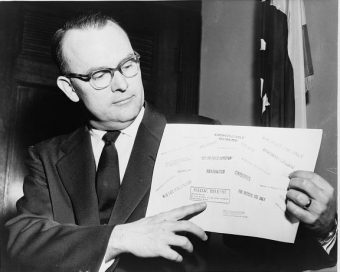

In 1952 a 37-year-old businessman named John E. Moss was elected to a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing California’s 3rd congressional district, which included his home city, Sacramento. Moss had lived a tough life: His mother died when he was twelve, and his father, an alcoholic and an unemployed coal miner, left shortly thereafter; Moss and his brother, both still young teens, were left to fend for themselves.

Then the Great Depression came.

Somehow, Moss not only survived those difficult years, but by 1938, through his hard work, he was the owner of a successful Sacramento appliance store. In 1948, after a stint in the Navy during World War II, he was elected to the California state assembly.

Over the course of two terms, Moss earned a reputation as someone who didn’t play the game the way it was “supposed” to be played. He didn’t go to lobbyists’ parties; he didn’t schmooze with party bosses—he just went to work. The focus of that work, not surprisingly, given his background, was fighting for the little guy. In 1952, after winning election to the U.S. Congress, it was time to take that fight for the little guy to Washington.

D.C.-CRETS

When Moss arrived in Washington in 1953, he quickly became acquainted with an issue that had been heating up over the previous few years: excessive government secrecy. During his first year on the job, 2,800 federal employees were fired for “security” reasons—meaning they were suspected of being Communists, or of having Communist leanings. (This was the height of the McCarthy Era.) Moss, a relatively liberal Democrat, had unfairly faced such accusations many times himself, and asked to see the fired employees’ records. He was refused. Those documents, he was told, were government secrets, and off limits, even to a member of Congress.

In 1955, after being elected to a second term, Moss decided to make government secrecy the main focus of his work. That same year, as a member of the powerful Government Operations Committee, he talked the committee chief into forming a Special Subcommittee on Government Information. Amazingly—for a still very junior member of Congress—he got himself appointed committee chairman. And so began what would become an 11-year mission: to open up the government to the people.

INFORMERICA

The struggle between government and citizens over access to information is as old as democracy itself. Which makes a lot of sense: The whole idea behind democracy is that ordinary citizens participate in the functioning of their government—and they can’t do that if they don’t know what the heck is going on. America’s founding fathers gave the average citizen a considerable boost in the battle over government secrecy. During the intense negotiations around ratification of the new country’s constitution Patrick Henry, of “Give me liberty or give me death!” fame, and one of the most outspoken proponents of open and transparent government, wrote in 1788:

The liberties of a people never were, nor ever will be, secure, when the transactions of their rulers may be concealed from them.

From these sentiments came such Constitutionally-enshrined rights as the freedom of the press and freedom of speech—which gave regular citizens legally protected rights to inquiry and criticism of government. But the founders also gave Congress the right to withhold information about its proceedings from the public. The criteria for determining what could be kept secret: Anything that “in their judgment require secrecy.” (It really does say that in Article I, Section 5, Clause 3, of the U.S. Constitution.)

FAST FORWARD

Remarkably, that was basically how things stayed for more than 170 years. The main reason for this, historians say, is that the U.S. government’s structure remained fairly simple and relatively small, for so long. In 1900, for example, there were still just eight U.S. federal government agencies (Treasury, Post Office, State, Agriculture, Labor, Justice, Interior, and War).

By 1940 the number of agencies had grown to 51. Because laws regarding public access to government hadn’t progressed as the government grew larger, by the late 1940s, there were big problems. The U.S. government, now a gargantuan and labyrinthine maze of an organization, had become a virtual black hole of government secrecy. And now people were starting to get upset about it.

MOSS GETS CROSS

In 1951, four years before John Moss formed his committee, the American Society of Newspaper Editors commissioned Harold L. Cross, legal counsel for the New York Herald Tribune, to investigate the issue of excessive government secrecy. In 1953 Cross’s report was published as a book titled The People’s Right to Know.

He wrote that virtually every part of American government operated under what amounted to an “official cult of secrecy”; that this secrecy had become a breeding ground for corruption; that it was leading to a rise in public mistrust in government; and that all of these things combined were doing serious damage to American democracy itself. Over the course of more than 400 pages, Cross made the case that Congress must craft new legislation that gave American citizens greater access to the inner workings of their government. In the early 1950s, The People’s Right to Know became a manual for the blossoming “freedom of information” movement, and in 1955 that movement finally got the champion it needed from inside the government: John Moss.

HEARING PROBLEMS

The Special Subcommittee on Government Information—soon dubbed “The Moss Committee”—began its investigations with a series of hearings in November 1955. Moss issued subpoenas; berated bureaucrats; interviewed journalists, professors, and constitutional law experts (including Harold Cross); he wrote volumes of reports; and basically made a big congressional pain of himself for the next 11 years. He simply refused to give up, even when fellow members of Congress tried several times to close down his committee by cutting its funding.

Here are just two of the many examples of excessive secrecy highlighted by the Moss Committee:

- During World War II, the U.S. Army did top secret work developing a particular new weapon, and information on the project remained classified until the committee exposed it in the late 1950s. The weapon: a new and improved bow and arrow.

- In 1959 the Postmaster General ruled that information about the salaries of postal employees (including him) was secret because the public was not “directly concerned” with such information. He also ruled that the public had no right to know the names of postal employees. (Those rules remained in effect until 1966.)

IT’S THE LAW!

By the mid-1960s, the burgeoning Civil Rights and Vietnam War protest movements had increased the public’s suspicion of government dramatically. As a result, the Moss Committee hearings became big news, and members of Congress—fearing for their jobs—finally got behind Moss. On October 13, 1965, the Freedom of Information Act, legislation based on the work of the Moss Committee, with language and recommendations taken directly from Harold Cross’s The People’s Right to Know, passed the Senate. On June 20, 1966, it passed the House—by a vote of 306 to 0. It was then sent on to President Lyndon Johnson.

Johnson hated the bill (he had made no secret of that). The other presidents in office during Moss’s 11-year campaign, Eisenhower and Kennedy, had felt pretty much the same as Johnson. But now the tide had turned and on July 4, 1966, Johnson, reluctantly, signed the bill into law. American citizens finally had a legal “right to know.”

FOY-YUH OWN GOOD!

So what exactly does the Freedom of Information Act, more commonly known by the acronym FOIA (and commonly pronounced foy-yuh) do? It creates a process through which anyone—journalists, activist organizations, universities, plain old citizens, and even non-citizens—can request documents from U.S. government agencies, and it requires those agencies to either produce those documents or provide a legal reason for not doing so.

- FOIA does not pertain to Congress or the courts. It deals with the executive branch of the federal government only. (This is primarily because, in terms of numbers of employees and agencies, the executive branch is much larger than the other two branches.)

- FOIA applies to federal “agencies,” but the term is applied broadly. FOIA can be used to access records from the White House; federal departments, such as the Departments of Defense and Education; independent agencies, such as the Veterans Administration and the CIA; and most other offices that fall under the control of the executive branch.

FOR YOUR INFORMATION…

- Since its passage in 1966, FOIA has been used millions of times to secure the release of classified government documents. It has been called one of the most important laws regarding the rights of citizens ever enacted in the U.S.—right up there with the Bill of Rights—and it has been used as a model for similar laws in countries all over the world.

- More than 650,000 FOIA requests were made in 2012 alone. Of those requests, 30,000 were denied outright, roughly half were granted in full, and the remainder were partially granted, meaning the documents turned over were partially redacted.

- John Moss was reelected 12 times, and served in Congress until 1979. After FOIA passed in 1966, he went on to champion consumer rights, and in 1972 he authored the landmark Consumer Product Safety Act. Moss died in 1997 at the age of 82.

- In 1766, ten years before the American Revolution, Sweden passed the “Freedom of the Press Act.” Among other things—it gave Swedish citizens access to uncensored government documents. And while Sweden was not a proper democracy at the time—and the law was suspended just six years later—it is recognized today as the first “freedom of information” law in history.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|