Who Invented the Bloody Mary Drink and Who is It Really Named After?

For many, Sundays mean brunch and a delicious morning cocktail. Quite often, that early alcoholic beverage is the odd combination of tomato juice, celery, hot sauce, Worcestershire sauce (see: The Stomach Turning Thing Worcestershire Sauce is Made Of), vodka and other spices that’s known as a “Bloody Mary.” While admittedly it’s pretty tasty, the recipe isn’t exactly intuitively good. So, who and how was this smorgasbord of a beverage ever concocted? And was it actually named after a 16th century queen who had the habit of burning people at the stake?

For many, Sundays mean brunch and a delicious morning cocktail. Quite often, that early alcoholic beverage is the odd combination of tomato juice, celery, hot sauce, Worcestershire sauce (see: The Stomach Turning Thing Worcestershire Sauce is Made Of), vodka and other spices that’s known as a “Bloody Mary.” While admittedly it’s pretty tasty, the recipe isn’t exactly intuitively good. So, who and how was this smorgasbord of a beverage ever concocted? And was it actually named after a 16th century queen who had the habit of burning people at the stake?

As the fifth of six children of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon (and the only one to survive infancy), Mary Tudor was pre-ordained as royalty when she was born in 1515. But it wasn’t easy for Mary, whose father had desperately wanted a son (which he did eventually have). When Henry VIII annulled his marriage to Catherine and instead wedded Anne Boylan (see: The Many Wives of King Henry VIII), Mary was declared “illegitimate.” Nonetheless, Mary still had a path to the throne and when her younger half-brother Edward VI died from tuberculosis at 15, it seemed she would become queen. However, due to Mary’s illegitimacy and fear she would convert the country back to Roman Catholicism, a plot was put in place to install Henry VIII’s niece, Lady Jane Gray, instead. After only nine days, public support for Mary was too strong and Grey was usurped. Queen Mary finally took her place upon the throne.

Mary’s brief five year reign as queen was violent and harsh. She turned the country back to Roman Catholicism and began an active campaign of open persecution of Protestants. Those who didn’t follow her strict heresy laws risked being burned on the stake. All in all, approximately 300 Protestants were killed during Mary Tudor’s reign, earning her the long-remembered nickname “Bloody Mary.”

While the moniker stuck, she was not unique among monarchs of the era in terms of executing people at will. In fact, Henry VIII executed not hundreds, but many thousands during his reign, but nobody bothered nicknaming him “Bloody Henry.” In the end, however, “Blood Mary’s” methods of forcing her nation to Catholicism were not effective, and, as so often happens, the victors color the events and people of history to their liking. After her death in 1558 from what some historians believe to have been prolactinoma along with ovarian cancer, the country returned to being Protestant.

Flash forward a few centuries later to the invention of the drink that may or may not bear her nickname. (We will get into that in a moment.) Now, there are two commonly accepted origin stories of the Bloody Mary drink, both of which have entered the annals of history as THE story behind the invention of the elixir, depending on what otherwise reputable source you want to consult. While both stories have plenty of holes in them, there is enough documented evidence to get a fair, though not perfect, idea of the genesis of the drink.

The first tale begins in an American bar in Paris. Opened on Thanksgiving Day in 1911 by an expat and horse jockey named Ted Sloan, the “New York Bar” at 5 Rue Daunou eventually became a hotspot for American soldiers during World War I. In 1923, Sloan sold the bar to Scottsman Harry MacElhone who was once a bartender at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. After purchasing it, Harry added his name to the bar, making it “Harry’s New York Bar.” The establishment is still there today.

Along with notable American guests like Rita Hayworth, Ernest Hemingway and Humphrey Bogart, a lot of Russian émigrés who had escaped the Russian Revolution also patronized the bar. One of Harry’s bartenders at the time was Fernand Petiot, who had risen up from kitchen boy at 16 to bartender. Realizing it was profitable to make cocktails with Russian vodka due to the new clientele, Petiot began experimenting with the hard liquid. Eventually, he found a match with canned “tomato juice cocktail.”

Along with notable American guests like Rita Hayworth, Ernest Hemingway and Humphrey Bogart, a lot of Russian émigrés who had escaped the Russian Revolution also patronized the bar. One of Harry’s bartenders at the time was Fernand Petiot, who had risen up from kitchen boy at 16 to bartender. Realizing it was profitable to make cocktails with Russian vodka due to the new clientele, Petiot began experimenting with the hard liquid. Eventually, he found a match with canned “tomato juice cocktail.”

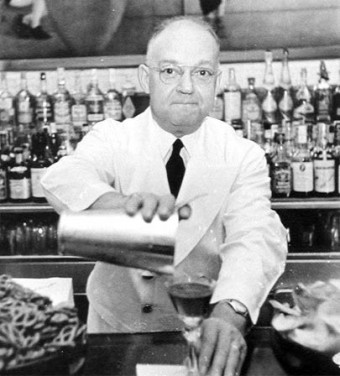

The customers loved the new drink – Russians, Americans and French – and voila, a popular drink was born. According to this version of things, Americans brought the Bloody Mary back Stateside and, soon, Petiot was offered a plum job being the main bartender at the King Cole Bar at the St. Régis Hotel in New York. He made the move in 1934 and remained one of the city’s most famed barkeeps until his retirement in 1966.

So what about the name- Bloody Mary? One legend has it that Petiot simply named it after Queen “Bloody” Mary Tudor as a dark joke in war-ravaged Europe. Another says the name was a suggestion from frequent customer, American entertainer Roy Barton, in homage to his favorite waitress, Mary, at the Chicago nightclub “Bucket of Blood.” The club’s name purportedly stems from the dirty, bloody mop water that the employees would throw in the streets after cleaning up after the violent nightly activities that happened at their establishment.

Whether that’s how that notorious nightclub really got its name or not, Petiot did state in an interview in January of 1972 with the Cleveland Press that it was indeed a customer who suggested the name “Bloody Mary” after the aforementioned waitress at the Bucket of Blood. However, there is no direct evidence backing up this assertion, mostly just a lot of vague recollections from events that happened many decades before. Human memory being what it is (and particularly factoring in our brains’ amazing ability to inject even very detailed false memories for a surprising amount of our recollections), it’s not clear whether this is really how the name came to be. (We’ll get into this more in a bit.)

What we do know for sure is that when Petiot started serving his drink in New York, at least as far as documented evidence reveals, he wasn’t calling it the “Bloody Mary.” Instead, he had dubbed it the “Red Snapper.” (One can still get a “Red Snapper” at the King Cole Bar today.) Supposedly he initially did call it the Bloody Mary but shortly after his arrival, the owner of the bar requested the name be changed, but there is no direct evidence to support this supposition.

The first known documented instance of it being called “Bloody Mary” didn’t occur until 1939 in an article in the Chicago Tribune, written by Walter Winchell. This was several years after Petiot came to the United States. On top of that, as noted by esteemed etymologist Barry Popik, later in the decade Petiot claimed he invented the Bloody Mary and gave it that name in Paris, Harry’s New York Bar in which he worked published a recipe book of its drinks- there is no mention of anything resembling a Bloody Mary, let alone any drink using the name.

Popik also notes skepticism in Petiot’s recollections owing to the fact that commercial canned tomato juice wasn’t a thing until the late 1920s- after Petiot claims he used a canned tomato juice cocktail as an ingredient in his drink. (It is possible Petiot’s recollection is mostly correct, with him simply getting his dates wrong. This would also, perhaps, explain the lack of reference to the drink in the 1920s Harry’s recipe book.) That said, the earliest surviving recipe of the drink under the name Bloody Mary didn’t come about until Lucius Beebe’s Stork Club Bar Book published in 1946. This particular reference also wasn’t crediting Petiot with inventing the drink, nor using his recipe. This brings us to the next widely cited origin story.

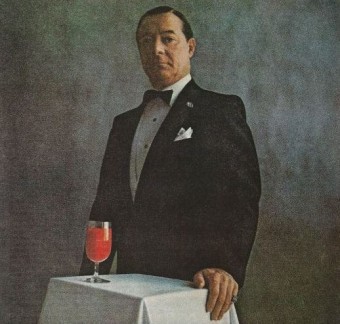

In this tale of how the Bloody Mary was invented, its creator was the “Toastmaster General of the United States” George Jessel. A famed vaudeville star, Broadway actor, comedian and master of ceremonies of his day, he claimed to have invented the drink in 1927, stating in his 1975 autobiography The World I Lived In,

In this tale of how the Bloody Mary was invented, its creator was the “Toastmaster General of the United States” George Jessel. A famed vaudeville star, Broadway actor, comedian and master of ceremonies of his day, he claimed to have invented the drink in 1927, stating in his 1975 autobiography The World I Lived In,

In 1927, I was living in Palm Beach, or on a short visit, I don’t remember which, where nearly every year I captained a softball team for a game against the elite of Palm Beach such as the Woolworth Donohues, the Al Vanderbilts, the Reeves, and their ilk….

Following the game myself, and a guy named Elliot Sperver, a Philadelphia playboy, went to La Maze’s and started swilling champagne. We were still going strong at 8am the next morning…. We tried everything to kill our hangovers and sober up. Then Charlie the bartender, enjoying our plight, reached behind the bar. “Here, George, try this,” he said, holding up a dusty bottle I had never seen before. “They call it vodkee. We’ve had it for six years and nobody has ever asked for it.”

I looked at it, sniffed it. It was pretty pungent and smelled like rotten potatoes. “Hell, what have we got to lose? Get some Worcestershire sauce, some tomato juice, and lemon; that ought to kill the smell,” I commanded Charlie. I also remembered that Constance Talmadge, destined to be my future sister-in-law, always used to drink something with tomatoes in it to clear her head the next morning and it always worked- at least for her.

“We’ve tried everything else, boys, we might as well try this,” I said as I started mixing the ingredients in a large glass. After we had taken a few quaffs, we all started to feel a little better. The mixture seemed to knock out the butterflies.

Just at that moment, Mary Brown Warburton walked in. A member of the Philadelphia branch of the Wanamaker department store family, she liked to be around show business people and later had a fling with Ted Healey, the comic. She had obviously been out all night because she was still dressed in a beautiful white evening dress. “Here, Mary take a taste of this and see what you think of it.” Just as she did, she spilled some down the front of her white evening gown, took one look at the mess, and laughed, “Now you can call me Bloody Mary, George!”

From that day to this, the concoction I put together at La Maze’s has remained a Bloody Mary with very few variations. Charlie pushed it every morning when the gang was under the weather. Now, about a year later, the benefit of Joe E Lewis was to be held at the Oriental Theater and I was sitting in my hotel room with Ted Healey before leaving for the theater. Ted, as usual, was slightly inebriated. He happened to pick up a copy of a Chicago paper and read an item in Winchell’s column. It said that I had named the Bloody Mary after Ted’s then steady girl, Mary Brown Warburton.

Ted turned white, “What the hell are you doing making a pass at my girl, you son of a bitch,” he yelled. And just as he did, he pulled out a pistol and tried to shoot me. I ducked and the shot missed, but as the pistol went within a foot of my right ear, I was completely deaf for a week. I had a hell of a job doing the benefit that night.

So which story is true? It would seem parts of both, with a pinch of misremembering mixed in, along with some ambiguity with regards to how close a recipe needs to be before you call it a Bloody Mary today.

You see, before either of these gentlemen claim to have invented the Bloody Mary (and before they definitely both helped popularize it), there were countless recipes for exceptionally similar drinks, sans alcohol. For instance, in the March 12, 1892 edition of the Hospital Gazette in London, it mentions a beverage served in a club across the pond in Manhattan that was made as follows:

For the benefit of those who may be possessed of suicidal intentions, I give the recipe. Seven small oysters are dropped into a tumbler, to which must be added a pinch of salt, three drops of fiery Tabasco sauce, three drops of Mexican Chili sauce, and a spoonful of lemon juice. To this mixture add a little horseradish, and green pepper sauce, African pepper ketchup, black pepper, and fill up with tomato juice.

Other similar recipes in the ensuing few decades before Jessel and Petiot added alcohol subtracted the oysters and added things like Worcestershire sauce. So it seems questionable that either of their recollections of how inspiration struck them to conjure up the otherwise rather odd concoction was perfectly accurate. In fact, in a 1955 Smirnoff vodka ad campaign, 58 year old Jessel wasn’t nearly so certain he had invented the Bloody Mary as 76 year old Jessel was while writing his autobiography.

In that 1955 ad campaign, he stated “I think I invented the Bloody Mary, Red Snapper, Tomato Pickup or Morning Glory…” He then goes on to describe in much less detail the events of creating the beverage, though in this case insinuating that he really just wanted to drink some “good Smirnoff Vodka” but felt he needed the nutrients of tomato juice, so slapped them together, “the juice for body and the vodka for spirit, and if I wasn’t the first ever, I was the happiest ever.”

Given the prevalence of similar known recipes of the age, minus the vodka, it is probably more likely that these two gentlemen were familiar with the basic cocktail and simply tweaked it slightly to their own liking and added alcohol, with the fact that they helped popularize it being why they are given the credit today. So who came up with their version first and who actually named it Bloody Mary?

It’s noted that Walter Inchell, the author of the aforementioned Chicago Tribune article which is the first documented mention of the drink being called “Bloody Mary” was a friend of Jessel’s. He stated in this first “Bloody Mary” reference that the drink was “vodka with tomato juice.”

A few months later in December of 1939, the aforementioned Lucius Beebe, whose 1946 recipe of the drink is the oldest known surviving named Bloody Mary recipe today, wrote in The New York Herald, “George Jessel’s newest pick-me-up which is receiving attention from the town’s paragraphers is called a Bloody Mary: half tomato juice, half vodka.”

Of course, the rub comes from when you want to start calling a drink with a certain set of ingredients a “Bloody Mary,” at least as far as we think of it today. In a 1964 interview with the New Yorker, Petiot himself elaborated on this, noting “I initiated the Blood Mary of today… Jessel said he created it, but it was really nothing but vodka and tomato juice when I took it over.”

And, indeed, the first known recipes for the drink seem to mostly back up Petiot’s claim. In the 1946 Stork Club Bar Book, Jessel’s recipe for the Bloody Mary was listed as “3 oz vodka, 6 oz tomato juice, 2 dashes of angostura bitters, juice of half a lemon.”

However, a half decade earlier, in Crosby Gaiges Cocktail Guide and Ladies Companion we have the first known documented instance of the recipe for Petiot’s Red Snapper which was sent to Crosby directly from an individual at Petiot’s place of work: “2 oz tomato juice, 2 oz vodka, 1/2 teaspoon Worcestershire, 1 pinch of salt, 1 pinch of cayenne pepper, 1 dash of lemon juice, salt, pepper and red pepper to taste.”

So, if you want to start calling a Bloody Mary a Bloody Mary if it has the minimum base ingredients of vodka and tomato juice, the credit would mostly lie with Jessel, as he claimed. But Petiot’s drink is closer to the general Bloody Mary recipe that we know and love today- it just was under a different name.

In either case, it would seem rather than a revolutionary new drink, both of these “Bloody Mary” recipes were more of an evolution of other very similar drinks being made at the time, with the primary contribution here being getting the ratios to each individual’s liking and then adding vodka and helping to popularize the mixtures.

As to the name, the leading candidates are Petiot’s 1972 recollection of a customer suggesting it be called “Bloody Mary” after a waitress at Chicago’s Bucket of Blood, and Jessel’s 1975 recollection of naming it after Mary Brown Warburton, daughter of department store magnate John Wanamaker.

Petiot’s claim has zero hard evidence to back it up and some, like that there is no documented evidence that he ever called it a Bloody Mary at any establishment he worked at and that the 1920s recipe book from the bar he claims to have invented it at did not mention the drink, that would seem to be a strike against his recollection. On the other hand, in the earliest known instances of the drink being called a Bloody Mary, Jessel is given credit for the drink, but technically not explicitly for the name, though in some instances it seems implied.

So we’re left in the very tenuous position of relying on either person’s 1970s recollection of how they came up with the name “Bloody Mary” way back in the 1920s, as our best, though decidedly unsatisfactory, evidence as to the origin of the name… Keeping in mind caveats concerning the extreme fallibility of human memory even after short periods, let alone decades, Jessel technically has the stronger claim given he at least has some contemporary evidence on his side with regards to the first documented instances of the name of the drink being used. So the slight edge, perhaps, goes to the drink being named after heiress Mary Warburton.

Whatever the case, no contemporary evidence points in any way to the 16th century Queen Mary being the inspiration for the name- that’s a supposition that didn’t come about until decades later. A similar popular incorrect assertion put forth by certain otherwise extremely reputable sources (nobody bats a thousand) is that the name was inspired by a character in the 1958 film South Pacific. This idea seems to have popped up owing to the fact that it was in the mid to late 1950s that the drink’s popularity really began to explode thanks to the 1950s Smirnoff ads featuring Jessel. But of course, the name of the drink pre-dates this film, and ad campaign, by a good margin.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- What Causes a Hangover?

- The Truth About the Origin of the Potato Chip

- Why Does James Bond Like His Martinis Shaken, Not Stirred?

- Origin of the Word “Cocktail” for an Alcoholic Drink

- The Origin of Toasting Drinks

- The Shockingly Recent Invention of Buffalo Wings and Why They are Called That

- The Big Apple- Bloody Mary Cocktail

- “Mary I” – History.com

- “Edward VI” – Britannia

- “Mary Tudor”- Biography.com

- “Prolactinoma” – Mayo Clinic

- Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink

- “The Bloody History of the Bloody Mary” by Jack McGarry – Gifford’s Guide

- The illness and death of Mary Tudor – Journal of the Royal Society Medicine

- “The Secret Origins of the Bloody Mary” – Esquire

- “The World I Lived In” by George Jessel

- “GEORGE JESSEL, COMEDIAN, DEAD; KNOWN AS ‘TOASTMASTER GENERAL'” – The New York Times

- “Bucket of Blood” – The Chicago Crime Scenes Project

- “BARMAN” by Geoffrey T. Hellman – New Yorker

- “Why Queen Mary Was Bloody” – Christianity Today

- Bloody Mary

- George Jessel

- Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink

- Smirnoff Vodka Ad

- Fernand Petiot

- Bucket of Blood

- Etymology Bloody Mary

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Please consider the following suggested corrections …

Quoting from the article:

“When Henry VIII annulled his marriage to Catherine and instead wedded Anne Boylan …”

I have never seen this spelling of “Boleyn.” I think that it is just a misspelling.

Quoting again:

“However, due to Mary’s illegitimacy and fear she would convert the country back to Roman Catholicism … She turned the country back to Roman Catholicism …”

The references to something non-existent — “Roman Catholicism” — constitute a common error found on the Internet, in printed publications, and in spoken English. I am shocked to see it continuing to be posted at “Today I Found Out,” even after I have asked that it be corrected on many occasions. [Please, owner of TIFO, tell all your writers to use the correct term — simply “Catholicism” — from now on, and find and fix all the TIFO pages that contain the error.]

Ironically, the term, “R…C…,” was coined in England at some point not long after 1535, when King Henry VIII began his persecution of the Church. It was used for centuries as an insult, falsely implying that Catholics were not loyal to the English monarchs but were loyal to a Roman monarch.

Nowadays, there are MANY Catholics who are unaware of this history and mistakenly refer to themselves as “R…C…,” not realizing that they are perpetuating the insult. Even they — not to mention non-Catholics — seem to be unaware of the fact that the Church NEVER refers to herself as “R…C…” — never in the sixteen documents of the great Second Vatican Council (of the 1960s), never in the “Code of Canon Law” (1983), and never in the “Catechism of the Catholic [sic] Church” (of the 1990s).

Compounding the confusion is that many “eastern” Catholics (those belonging to “ritual churches” based in eastern Europe, the Middle East, India, etc. — such as Byzantine Catholics) WRONGLY refer to their fellow Catholics of the “west” as “Roman Catholics.” Thus, they wrongly call part of the Catholic Church “R…C…,” while some protestants (and some Catholics) wrongly call the entire Catholic Church “R…C…”. It would be nice if these errors could end.

Quoting a third and final time from the article …

“A similar popular incorrect assertion put forth by certain otherwise extremely reputable sources … is that the name was inspired by a character in the 1958 film South Pacific. … But of course, the name of the drink pre-dates this film, and [the Jessel] ad campaign, by a good margin.”

The writer didn’t do his “homework.” The 1958 movie, “South Pacific,” was based on the Broadway musical that premiered in 1949 … and the musical was based in part on the 1946 James Michener novel, “Tales of the South Pacific,” in which Bloody Mary is a character. One source says that Michener was aware of a real woman (of an island or mainland Asia) that had that nickname and was involved in a bloody revolt. I will not claim that the drink was named after her, but only that the nickname goes back to a time (at least several years) before the Jessel ad campaign.

To quote your comment – “he references to something non-existent — “Roman Catholicism” — constitute a common error found on the Internet, in printed publications, and in spoken English. I am shocked to see it continuing to be posted at “Today I Found Out,” even after I have asked that it be corrected on many occasions. [Please, owner of TIFO, tell all your writers to use the correct term — simply “Catholicism” — from now on, and find and fix all the TIFO pages that contain the error.]

Ironically, the term, “R…C…,” was coined in England at some point not long after 1535, when King Henry VIII began his persecution of the Church. It was used for centuries as an insult, falsely implying that Catholics were not loyal to the English monarchs but were loyal to a Roman monarch.

Nowadays, there are MANY Catholics who are unaware of this history and mistakenly refer to themselves as “R…C…,” not realizing that they are perpetuating the insult. Even they — not to mention non-Catholics — seem to be unaware of the fact that the Church NEVER refers to herself as “R…C…” — never in the sixteen documents of the great Second Vatican Council (of the 1960s), never in the “Code of Canon Law” (1983), and never in the “Catechism of the Catholic [sic] Church” (of the 1990s).”

First off – before the Reformation, “Roman” Catholic was used to differentiate from “Orthodox” Catholic (a usage that hasn’t been commonly used for centuries, it’s been altered to just “Greek Orthodox” and “Russian Orthodox” without the “Catholic” part added on anymore). The two churches each saw themselves as the “proper” Catholic church (Catholic meaning “universal”) and differentiated the other with the use of “Roman” for the Westerners and “Orthodox” for the Easterners – roughly, of course (it’s a comment, not a religious dissertation – if you want semantics, google it). Admittedly, Westerners didn’t refer to themselves as “Roman Catholic,” Easterners did (and vice versa). So you’re right about the part about it not being widely used in English/England until Henry VIII and the Reformation – when Henry needed to differentiate between the Western Catholic church and his new Anglican Church, he (and his lackey’s) started using the Easterners designation of “Roman” Catholic. (Obviously Henry, his lackeys, and the populace of England gave little thought to the “Orthodox” Catholics in Russia/Greece/East, but for the “technicalities” of the whole issue the point was that Henry was arguing with the Pope in Rome, not the Patriarch in Istanbul/Constantinople/Athens so they started using the under-used in the West term “Roman Catholic” to specify that Henry hadno particular beef with the “Orthodox” Catholics, though he wasn’t willing to convert to or spread “Orthodox” Catholicism [cause he still wouldn’t have been allowed to divorce anyone…]. Basically, the widespread usage of the term “Roman Catholic” came about in English because Henry didn’t feel the need to piss off TWO different leaders of TWO different but similar religions. He was only aiming to piss off the Catholics from Rome – hence “Roman Catholic,” making it clear he was angry at the Pope in Rome, not Catholic leaders as a whole).

Admittedly, since Henry VIII reigned we’ve seen drastic changes to all religions, including Eastern Orthodoxy churches, as well as the Catholic Church – and most people, especially in the West, are unaware that “technically” the Eastern Orthodox Churches are “catholic” churches. But during the time of Henry VIII, it was a very important distinction to make – he was breaking from Rome, he was breaking from the Catholic Church based out of Rome, therefore he was breaking from the “Roman” Catholic Church. It’s not an error – it’s an age-old usage of a word that was once highly relevant but is no longer. It was very, very important for Henry VIII to differentiate between the “Roman” Catholic Church and the other Catholic Churches of the time – it’s the difference between the (now) Orthodox Patriarch staying out of a disagreement that doesn’t include him or the Patriarch joining forces with the Pope to take Henry down.

But yes, the propaganda strewn about throughout Henry VIII’s reign and thereafter implied that Catholics would stay loyal to the Pope in Rome rather than the King in London. Though your use of “monarch” for Rome is misleading – the Catholics weren’t loyal to the *King* in Rome, JUST the Pope (who was NOT a monarch in name – in practice, maybe, but no one ever, ever called the Pope the King). So the use of “Roman” became *both* a specification to prevent other churches from getting in Henry’s face and later a slur to imply that they weren’t loyal to London.

And no, Rome isn’t any more likely to refer to themselves as the “Roman Catholic” church anymore than Orthodoxy in Russia refers to themselves as “Russian Orthodox.” In Russia, they are just “Orthodox” or “Church” or whatever Russian is for “Catholic” – same goes for Greece; they don’t refer to their church as the “Greek Orthodox Church,” they’re “Orthodox” or “Church” or “Catholic” in Greek. Just like the Vatican specifies between “Greek” Orthodox or “Russian” Orthodox when required, Russian Orthodox would refer to the religion of the Vatican as “Roman” Catholic (because it’s “Roman” not “Russian”). It’s as much a place-name as it is a slur – it certainly started as such, a simply way to differentiate between the (then common) Eastern Catholics and Western Catholics, so that the Eastern Catholic Patriarch(s) wouldn’t get too uppity with Henry telling off their Western peer the Pope. In that way, it helped lessen any sanctions against England the Pope tried to put in place – the West certainly tried to follow through with the Pope’s sanctions (for a time…) but the East stayed out of that little tiff because by referring to the “Roman” Catholic Church Henry was hedging his bets and didn’t give the East a good reason to join in on the Pope’s side by making it clear his issues were with Rome, and the Pope, and no one else.

TL;DR – the alterations in the English language since the Elizabethan era make your comment superfluous. You’re not *completely* wrong, but neither are you *completely* right. And no doubt I’m neither, as well. But it’s FAR too complicated to simply say that the usage of “Roman” Catholic is ENTIRELY incorrect. It’s not – at the time Henry VIII started using it in English, the differentiation of the “Roman” Catholic Church from the “Eastern” Catholic Churches was essential to ensuring ALL the Catholics (wherever they may be living) didn’t gang up on Henry (and England) while he was arguing specifically with the Catholic in Rome (the Roman Catholics – he had no beef with the “Eastern” Catholic, just Rome). Basically, he was saving his ass by specifying the “Roman” Catholics, those with whom he was fighting with. The Catholics in Rome = Roman Catholics.

I seem to remember the New York Times running a competition on this subject back in the ’80s, starring the usual suspects plus one or two not listed here. In the end the most plausible was that the drink was indeed invented in a New York bar, but one in which the bartender was a Russian named Vladimir. The concoction was known simply as Vladimira, the genitive form of Vladimir, and Anglicised by the inebriated customers to Bloody Mary. Perhaps another of your readers can recall more detail

No Caesar variation? Really? No mention whatsoever of the wonderful Canadian drink derived from the Bloody Mary? I’m disappointed 🙁

(I’m pretty sure the only difference is the use of clam juice and tomato juice, instead of just tomato juice. Though the Caesar has become so popular in Canada that for as long as I can remember Mott’s has sold a “Clamato” juice in Canada for the ease of bartenders everywhere! Which is good on it’s own, as well as for making a “Clam Eye” which is just a Clamato variation of the Red Eye – beer and tomato juice.)

Caesar’s are delicious – next time anyone’s in Canada try a Caesar at your local bar. They’ll know the recipe! There are likely some American bars that can make it, I just don’t know any of the top of my head. Somewhere a lot of Canadians congregate would be a good bet!