Forgotten History: the Story of Emma Sharp and the Barclay Challenge

In 1809, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice made a bet with one of his pedestrian rivals, Sir James Webster-Wedderburn, that he could walk 1,000 miles (about 1,609 kilometers) in 1,000 hours. The wager? 1,000 guineas. To get around the major problem of needing to rest, Barclay figured if he walked back to back miles–a mile at the end of one hour and another at the beginning of the next–and repeated this strategy throughout the race, he would be able to rest in approximately 90 minute intervals throughout the near 42 day long race.

In 1809, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice made a bet with one of his pedestrian rivals, Sir James Webster-Wedderburn, that he could walk 1,000 miles (about 1,609 kilometers) in 1,000 hours. The wager? 1,000 guineas. To get around the major problem of needing to rest, Barclay figured if he walked back to back miles–a mile at the end of one hour and another at the beginning of the next–and repeated this strategy throughout the race, he would be able to rest in approximately 90 minute intervals throughout the near 42 day long race.

It worked. He completed the walk on July 12, 1809, 42 days after it commenced. The 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours walking feat became widely known as the “Barclay Match”.

While any sort of race involving simply walking at a leisurely pace may sound easy, walking 1,000 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours is anything but. Beyond the physical toll on the body, the lack of consistent prolonged sleep over a six-week period and the lack of doing anything but walk around in circles takes a major mental toll. After Barclay, many pedestrians attempted the same feat of feet and failed, but it wasn’t until a female Australian attempted the Barclay Match and failed that the opportunity unfolded for another women to make history.

Due to the ideology of this era that women were extremely frail, they were strongly urged (and sometimes forced) to not partake in strenuous activity such as sporting competitions. For instance, 17 year old Yankee minor leaguer Jackie Mitchell once struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig back to back on just seven pitches, five of them of the swing and miss variety; the next day, she was banned from major and minor league baseball by commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis who stated his reason for doing so was because baseball was “too strenuous” for women. (This purported frailty hadn’t stopped Lizzie “The Queen of Baseball” Murphy from enjoying an extremely lucrative 23 year career as a professional baseball player, during which she became the first person, man or woman, to play for both the National League and American League All Star teams.)

In any event, long before the Queen of Baseball was making a laughingstock of the idea of women being too “delicate” to play sports, in 1864, Emma Sharp heard about the aforementioned Australian woman’s failed attempt at the Barclay Match. Mrs. Sharp, who was then in her early thirties, subsequently declared to her husband, John, that she thought she could do it. John was reportedly not so enthusiastic, stating that walking 1,000 miles was hardly an appropriate task for a woman to undertake.

Undeterred and despite that she’d not actually trained for the event at all, Emma proceeded with her conviction and started making plans for the event. She was fortunate enough to enlist the help of the landlord of the Quarry Gap Hotel, at Laisterdyke, England, who enthusiastically offered up the grounds attached to his hotel as the location of the course. In exchange, he would receive a percentage of the money earned from ticket sales, and no doubt do great business from all the spectators.

While the fact that anyone would pay to see someone walking around in circles for days on end may seem strange to us, at the time, competitive walking, or pedestrianism, was one of the most popular spectator sports in the Western world, with certain matches drawing tens of thousands of spectators. Yes, before the internet and TV, our forebears found watching people walk in circles for hours on end an ideal excuse to get together and socialize, in some respects not too dissimilar from NASCAR, but without the occasional flaming crashes.

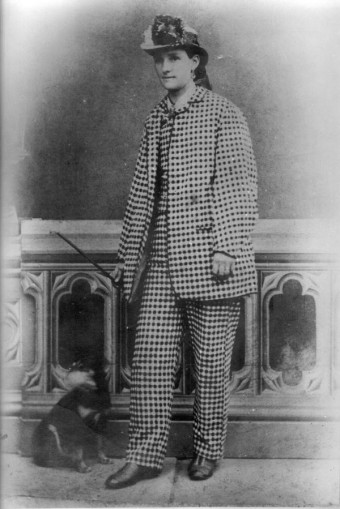

As for Sharp’s walk, it was likely to draw bigger crowds than most given that she was a woman attempting a physical feat that most of her compatriots of the male persuasion couldn’t do. To make the whole thing even more scandalous in the eyes of contemporaries, Emma decided to dress like a man for the event, a sensible choice given the typical garb of Victorian era women.

And so it was that on September 17, 1864, Emma Sharp took the first step of her 1,000 mile venture. She took the same approach as Captain Barclay by walking a roped off course of 120 yards for 30 minutes at a time, which was equivalent to about two miles, before taking a 90-minute break. She would continue this routine for six weeks straight, walking day and night, until she completed her last mile. As expected, since no woman had ever successfully completed this journey, and few men, Emma’s progress was widely reported in the newspapers and watched closely by supporters and critics alike, with tens of thousands of people turning up at various times to watch her put one foot in front of the other again and again.

As was popular with all such pedestrian events, many started making bets as to whether or not she would actually be able to finish. With the odds heavily against her at first, as the days wore on and it began to look like she might actually do it, malicious attempts to thwart her progress began. Beyond near constant jeering to break her spirit, about a week before she was scheduled to finish the 1,000 miles, unidentified individuals attacked her with chloroform to rough her up a bit, hoping this would inspire her to quit. She didn’t.

Others threw burning embers in her path, some tried to drug her food, and still others simply resorted to trying to trip her at random times. As things escalated, for her protection, eighteen police officers disguised as working citizens were assigned to her on the final days of the race. In addition to that, during the night, a helpful citizen walked in front of her with a loaded rifle. Emma also walked the final two days with a pistol, which she had to fire in warning a reported 27 times in total to ward off unruly spectators.

On October 29, 1864, at approximately 5:15 a.m., Emma Sharp became the first woman to complete the Barclay Challenge. Despite the general belief that women were too frail for such physical activity and despite her complete lack of training, the only major physical issue she experienced during the walk was painfully swollen ankles in the early going, but the problem ultimately went away as the days went on.

Over the course of the six straight weeks she walked, it was estimated that a total of over 100,000 people turned up at one point or another, with about 25,000 being present to watch her cross the finish line. Despite the fact that the locals celebrated Emma’s success by organizing a band to play on her final day and roasting an ox in her honor, Emma’s husband reportedly hid in the pub, embarrassed by his wife’s antics. He got over his shame pretty quickly, however, using the substantial funds she earned from ticket sales to quit his job at the Bowling Iron Works and open a rug making business.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Women Fainted So Much in the 19th Century

- How Did the Practice of Women Jumping Out of Giant Cakes Start?

- The Surprisingly Recent Time Period When Boys Wore Pink, Girls Wore Blue, and Both Wore Dresses

- The Woman Who Survived All Three Disasters Aboard the Sister Ships: the Titanic, Britannic, and Olympic

- How One of the Most Beautiful Women in 1940s’ Hollywood Helped Make Certain Wireless Technologies Possible

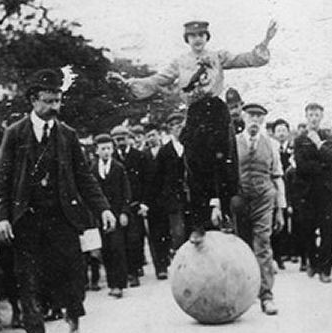

- Another famous female walker was one “The Lady Globe Walker”, Mademoiselle Florence, who, among other pedestrian accomplishments, managed to walk from London to Brighton, a distance of about 70 miles or 110 km, in just 3 days and 22 hours. Why is this impressive? She walked the whole way balancing atop a globe.

- Another famed female pedestrian was one Ada Anderson. Ada didn’t just walk, she entertained. She accompanied her jaunts with singing, public speaking spectacles, and pranks (usually on sleeping spectators). Ada’s most famous event was walking a quarter mile in 15 minutes… for 2700 consecutive quarter-hours- a little over 28 days straight. Presumably besides being hailed one of history’s greatest pedestrians, she might also aptly be named the Queen of Catnaps.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I’m confused about this. Is it walk 1 mile every hour for 1,000 hours? Or is it walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours? If its the latter, then I don’t see the big deal about rest. You can easily walk 20 or so miles in a day, then sleep for 8 hours and do it again.

The challenge was to walk exactly one mile in each of one thousand consecutive hours. That was equal to twenty-four miles each day, BUT … it was NOT acceptable to walk those twenty-four miles in, let us say, six hours — and then sleep for eighteen hours.

As hinted in the article, above, the winners of the challenge may have walked each of their hourly miles at a speed of four miles per hour, not easy, but feasible for someone in good health. This would require fifteen minutes of walking and would allow for forty-five minutes of napping. The challenge-winners, however, would walk TWO miles straight (requiring thirty minutes), followed by ninety minutes of napping to fill out each two-hour period. The first mile would be covered during the LAST fifteen minutes of the first hour, and the second mile would be covered during the FIRST fifteen minutes of the second hour — so they would stay within the rules of the challenge.

What’s your point… Armchair Ref…