This Day in History: November 10th- In Which We Discuss Henry Wirz, the Civil War, and the Notorious Andersonville Prison

This Day In History: November 10, 1865

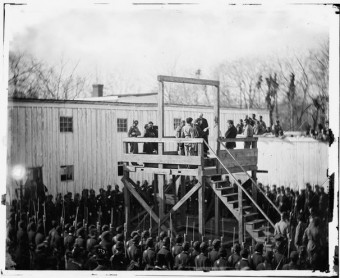

On November 10, 1865, Henry Wirz, the commander of Andersonville prison in Georgia (a.k.a. Camp Sumter), was executed for his actions during the Civil War. A Swiss immigrant, Wirz was the only Confederate officer convicted and put to death for war crimes. (Even Confederate President Jefferson Davis ultimately got off more or less scot free, See: What Ever Happened to Jefferson Davis?)

On November 10, 1865, Henry Wirz, the commander of Andersonville prison in Georgia (a.k.a. Camp Sumter), was executed for his actions during the Civil War. A Swiss immigrant, Wirz was the only Confederate officer convicted and put to death for war crimes. (Even Confederate President Jefferson Davis ultimately got off more or less scot free, See: What Ever Happened to Jefferson Davis?)

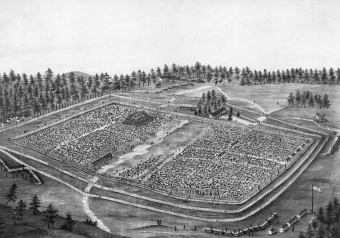

Built in 1864, Andersonville, or Camp Sumter, was the largest Confederate military prison. The original plan was to move the prisoners out of Richmond, Virginia to an area of greater security and a better food supply. The camp was operational for only a little over a year, but during that time over 45,000 Union soldiers were incarcerated there. Out of those, a full 13,000 perished from disease, starvation, exposure, and the general horrible conditions at the camp.

The first prisoners came to Andersonville in early 1864. Over the next few months, around 400 more arrived each day. At its peak, 33,000 prisoners were held in an area originally built to hold about 10,000.

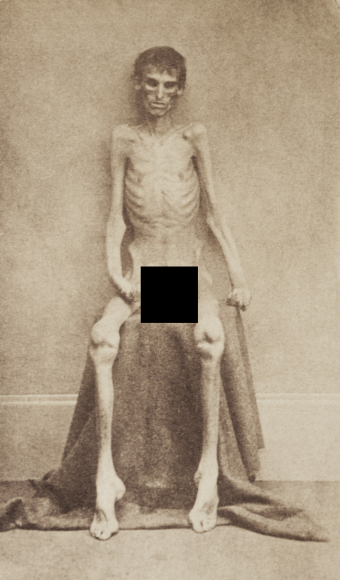

A small stream was the only source of water for prisoners, and it became a toxic cesspool of waste, being used for the latrine, the garbage dump (including for two Confederate camps nearby), bathing and drinking water. Plans for barracks were scrapped due to lack of resources, and the men’s only shelter was scrap wood and blankets on the ground. A prisoner from Michigan named John Ransom wrote in his diary: ‘With sunken eyes, blackened countenances from pitch pine smoke, rags, and disease, the men look sickening. The air reeks with nastiness.”

Sargent Major Robert H. Kellogg described his first impression upon being imprisoned at the camp on May 2, 1864,

As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that He alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.

Reverend William Hamilton who worked at the camp for a time noted of his first impression of the facilities,

I found the stockade extremely filthy; the men all huddled together and covered with vermin.… I found [the hospital] almost as crowded as the stockade. The men were dying there very rapidly from scurvy…diarrhea and dysentery…They were not only covered with the ordinary vermin but also maggots…they had nothing under them at all except the ground.

The man overseeing all of this was Henry Wirz. Wirz moved to Louisiana from Switzerland in 1849 and became a physician. When the Civil War began, he joined the Fourth Louisiana Battalion. Wirz was acting as a prison guard in Richmond, Virginia after the first Battle of Bull Run when Inspector General John Winder promoted him to working with prisoners of war. His duties included commanding a prison in Alabama, handling prisoner exchanges with the Union, and escorting POWs around the South. After an official trip to Europe, Wirz was given the task of running the new prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia called Camp Sumter.

The man overseeing all of this was Henry Wirz. Wirz moved to Louisiana from Switzerland in 1849 and became a physician. When the Civil War began, he joined the Fourth Louisiana Battalion. Wirz was acting as a prison guard in Richmond, Virginia after the first Battle of Bull Run when Inspector General John Winder promoted him to working with prisoners of war. His duties included commanding a prison in Alabama, handling prisoner exchanges with the Union, and escorting POWs around the South. After an official trip to Europe, Wirz was given the task of running the new prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia called Camp Sumter.

Andersonville had precious few resources, and as the Confederacy’s chances for victory began to wane, their already meager stores of food and medicine also dwindled. The soldiers and civilians of the South were having a hard time getting enough to eat as it was; providing for prisoners of war wasn’t tops on the South’s priority list.

This particularly became a problem for the South when the Union refused to continue prisoner exchanges in 1864. The reasoning behind this was that the Union Army knew that among the many resources the South was lacking at the time, manpower was high on the list. Thus, by keeping any captured prisoners, they not only diminished the South’s supply of soldiers, but also put extra strain on their resources via the South having to support more Union POWs. Little did they know of the horrible price the POWs in the South were paying.

Unsurprisingly, when the conditions at the camp were widely discovered by Northerners, they were less than pleased. Poet Walt Whitman, after getting a look at some of the survivors of the camp, wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.”

After the war, Captain Henry Wirz was charged with conspiring with other Confederate officers to “impair and injure the health and destroy the lives … of Federal prisoners” and “murder in violation of the laws of war.”

While it’s true that the prisoners under Wirz command were ill-treated to the extreme, it isn’t clear whether any of this was Wirz’ fault or if he could have done anything to improve the situation, and today many historians consider him more of a scapegoat than anything. In fact, Wirz attorney would later note that the night before his execution, Wirz was (supposedly) offered a deal- if he would implicate Confederate President Jefferson Davis as the responsible party for the war crimes committed at the camp, Wirz would be pardoned. Wirz told his attorney when learning of this offer, “Mr. Schade, you know that I have always told you that I do not know anything about Jefferson Davis. He had no connection with me as to what was done at Andersonville. If I knew anything about him, I would not become a traitor against him or anybody else even to save my life.”

Of the 160 witnesses who gave their testimonies in Wirz’ trial, many came from former prisoners describing the abhorrent conditions in the camp. Some blamed Wirz for this, even noting that he personally treated prisoners violently and occasionally withheld food for no good reason, but other survivors stated that Wirz simply hadn’t been given the resources to adequately provide for the prisoners. Needless to say, it was difficult to separate fact from fiction in the trial.

Perhaps the most notable witness in Wirz’ defense was Robert E. Lee, who noted that, in his opinion, Wirz had done the best he could with the extremely scant resources he was given.

Further backing up this notion was “the Angel of Andersonville” Father Peter Whelan. Whelan had worked in the camp for several months from sunup to sundown helping prisoners in whatever way he could, including attempting to leverage what small resources the local Catholic churches had to help the POWs. Most notably, Whelan personally borrowed $16,000 in Confederate money from one Henry Horne of Macon to acquire approximately ten thousand pounds of wheat flour, which was then baked into bread and distributed among the starving prisoners.

One former prisoner of Andersonville said of Whelan, “All creeds, color and nationalities were alike to him… He was indeed the Good Samaritan.” Sergeant John Vaughter went on to state that, “of all the ministers in Georgia accessible to Andersonville, only one could hear this sentence, ‘I was sick and in prison and you visited me,’ and that one is a Catholic [Peter Whelan].”

Whelan, along with the aforementioned Reverend Hamilton who also worked in the camp, stated that, apart from yelling at prisoners on occasion (such as swearing at new prisoners and threatening to shoot them if they tried to escape), they had never witnessed nor heard of Wirz himself inflicting any actual physical harm on any prisoner. This is something they felt they would have known about had it happened given their daily life of going around talking with the prisoners. (That said, punishments in the camp for breaking rules were reportedly severe, though it’s not clear whether they were any more severe than any other POW camp in the war.) They also stated that Wirz had been eager for their help in the camp and in their opinion was simply a man who was given far too few resources to manage his charges.

Beyond evidence Wirz produced at his trial showing he pleaded with his superiors on several occasions for more supplies to improve the conditions in his camp, in July of 1864, Wirz conscripted five of his prisoners and sent them North to appeal to the Union to reinstate the prisoner exchanges, telling them to describe to the Union officials the appalling conditions in Andersonville. To corroborate the story, he also had many other prisoners sign a petition. Unfortunately, the Union rejected the appeal and Wirz’ attempt to reduce the population of his prison camp failed.

So while it’s difficult to determine today whether Wirz really was the villain he was ultimately portrayed as (his camp had the highest rate of casualties of any of the Confederate POW camps, though this could have simply been a function of its enormous size- by population there were only four cities in the Confederacy larger than this POW camp), it is at least clear he was something of a sacrificial lamb and a focal point for Northern anger. Among his final words were (to the commanding officer overseeing his execution on November 10, 1865), “I know what orders are, Major. I am being hanged for obeying them.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Story Behind the Man Who was Killed in the Famous “Saigon Execution” Photo

- A Larger Conspiracy: The Failed Assassinations of Seward and Johnson

- The North’s Air Force During the American Civil War

- Did the Battle of Gettysburg Really Begin as a Search for Shoes?

- “The [American Civil] War Began in My Front Yard and Ended in My Parlor.”

Bonus Facts:

- In the late 1860s, close to death, Father Whelan finally managed to pay off the debt he’d incurred borrowing money for wheat for the POWs. He first petitioned Edwin Stanton, the Union Secretary of War for the funds, but Stanton replied that he would need documented proof of the purchase of the wheat flour given to the Union POWs. Whelan noted that he had “neither the health nor the strength …to run over Georgia to hunt up vouchers and bills of purchase.” As his health continued to decline due to a lung disease, Whelan’s doctor recommended he travel North to a less humid environment. Donations were given to provide the funds for this trip and accommodations upon his arrival, but instead of using them to travel to a more hospitable environment for himself, Whelan used them to pay off the wheat flour debt. He ultimately died on February 6, 1871 at the age of 69.

- One of the earliest known instances of the term “deadline” appeared in the minutes of the Trial of Henry Wirz: “And he, the said Wirz, still wickedly pursuing his evil purpose, did establish and cause to be designated within the prison enclosure containing said prisoners a ‘dead line,’ being a line around the inner face of the stockade or wall enclosing said prison and about twenty feet distant from and within said stockade; and so established said dead line, which was in many places an imaginary line, in many other places marked by insecure and shifting strips of [boards nailed] upon the tops of small and insecure stakes or posts, he, the said Wirz, instructed the prison guard stationed around the top of said stockade to fire upon and kill any of the prisoners aforesaid who might touch, fall upon, pass over or under [or] across the said ‘dead line’…”

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Quoting the article:

“On November 10, 1865, Henry Wirz, the commander of Andersonville prison in Georgia (a.k.a. Fort Sumter), was executed for his actions during the Civil War.”

Yikes! What an error! Andersonville Prison’s alternate name was CAMP Sumter, not FORT Sumter. Fort Sumter was in another state — South Carolina (on an island in Charleston harbor) — and was the site of the Civil War’s first battle.

I am amazed that neither the writer nor the owner/editor of this site nor any reader (over the course of several months) noticed this.

~~ Is it possible that the author wrote the essay but never read it before submitting it?

~~ Is it possible that the owner posted it without reading it attentively?

~~ Is it possible that I was the first outsider to ever even read the page?

This is all deeply troubling.

@Gecik: Good catch. We listed it correctly in two instances in the article but typoed it in the first. Thanks for letting us know. 🙂