This Day in History: September 28th- The End of Pompey the Great and the Birth of an Empire

This Day In History: September 28, 48 BCE

On September 28, 48 BCE, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey the Great, was assassinated on the order of King Ptolemy XIII of Egypt, who in turn was trying to earn Brownie points with Caesar.

On September 28, 48 BCE, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey the Great, was assassinated on the order of King Ptolemy XIII of Egypt, who in turn was trying to earn Brownie points with Caesar.

Pompey was born in northern Italy in 106 BCE. He began his career in the Roman Army and quickly began racking up victories and triumphs. During his illustrious career where he earned the moniker “The Great,” Pompey put down the Spartan slave revolt, rid the Mediterranean of pirates and conquered Palestine, Armenia and Syria.

In 60 BCE, Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, three of the most powerful and influential men in Rome, formed the first triumvirate. In a politically expedient move, Pompey divorced his wife Marcia to marry Caesar’s daughter, Julia. This did little to forge a stronger bond between the men. One could hardly say the three enjoyed each others’ company; their union was tenuous at best.

Tensions had started to reach critical mass within the triumvirate and things started to completely unravel when Pompey’s wife Julia, (who, as we remember, was also Caesar’s daughter) died during childbirth in 54 BCE. This caused Pompey considerable grief, for although his marriage was a political one, he had reportedly grown to genuinely love his wife.

Julia’s death gave Caesar the green light to treat Pompey as dastardly as he wanted to with no fear of hurting his daughter. Since Crassus had died in Parthia the year after Julia’s death, it was a showdown between Caesar and Pompey that led to civil war.

Cicero commented of this: “It is a struggle between two kings, in which defeat has overtaken the more moderate king [Pompey], the one who is more upright and honest, the one whose failure means that the very name of the Roman people must be wiped out …”

So it was that Caesar crossed the Rubicon with a legion of his soldiers, which was against Roman law. Specifically, Governors of Roman provinces (promagistrates) were not allowed to bring any part of their army within Italy itself and, if they tried, they automatically forfeited their right to rule, even in their own province. The only ones who were allowed to command soldiers in Italy were consuls or preators. This act of leading his troops into Italy would have meant Caesar’s execution and the execution of any soldier who followed him, had he failed in his conquest.

Caesar was initially heading to Rome to stand trial for various charges, by order of the Senate. According to the historian Suetonius, Caesar wasn’t at first sure whether he’d bring his soldiers with him or come quietly, but he ultimately made the decision to march on Rome.

Shortly after the news hit Rome that Caesar was coming with an army, many of the Senators, along with the consuls G. Claudius Marcellus and L. Cornelius Lentulus Crus, and Pompey, fled Rome. They were under the impression that Caesar was bringing nearly his whole army to Rome. Instead, he was just bringing one legion, which was largely outnumbered by the forces Pompey and his allies had at their disposal.

Nevertheless, they fled and after a lengthy struggle, Caesar was victorious and Pompey high-tailed it to Egypt, hoping his ties with the previous Pharaoh would ensure him the protection of his son, 13-year-old Ptolemy XIII.

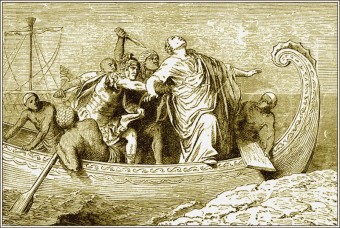

Pompey waited offshore for word from Ptolemy. It came in the form of two Romans who once fought by his side escorting him into a smaller vessel, ostensibly to meet with the Pharaoh. Instead, the two men both literally and figuratively stabbed Pompey in the back, beheaded him, stripped him naked and left his nude body rudely unattended on the shore.

Young Ptolemy’s advisors had counseled him that that old loyalties to a vanquished leader paled in comparison to a force-to-be-reckoned-with like Julius Caesar. Pompey’s head was delivered to Caesar, who reportedly was not pleased with the dishonorable way Pompey had been killed and what had been done to his body after. He ordered the assassins executed and a proper cremation for the head of his old frenemy.

Caesar then became Dictator Perpetuus of Rome. This appointment and changes within the government that happened in the aftermath ultimately led to the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- That Time Julius Caesar was Kidnapped by Pirates

- The Truth About Gladiators and the Thumbs Up

- Damnatio Memoriae: When the Romans Purposely Erased People from History

- The Truth About Nero and Fiddling While Rome Burned

- Et Tu Brute? Not Caesar’s Last Words

Bonus Fact:

Interestingly, despite the Rubicon once signifying the boundary between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy proper, the exact location of the river was lost to history until quite recently. The river’s location was initially lost primarily because it was a very small river, of no major size or importance, other than as a convenient border landmark. Thus, when Augustus merged the northern province of Cisalpine Gaul into Italy proper, it ceased to be a border and which river it was exactly gradually faded from history.

Thanks to occasional flooding of the region until around the 14th or 15th centuries, the course of the river also frequently changed with very little of it thought to still follow the original course, excepting the upper regions. In the 14th and 15th centuries, various mechanisms were put in place to prevent flooding and to regulate somewhat the paths of many rivers in that region to accommodate agricultural endeavors. This flooding and eventual regulation of the rivers’ paths further made it difficult to decipher which river was actually the Rubicon.

Various rivers were proposed as candidates, but the correct theory wasn’t proposed until 1933, namely what now is called the Fiumicino with the crossing likely being somewhere around the present day industrial town of Savignano sul Rubicone (which incidentally was called Savignano di Romagna, before 1991). This theory wasn’t proven until about 58 years later in 1991 when scholars, using various historical texts, managed to triangulate the exact distance from Rome to the Rubicon at 199 miles (320 km). Following Roman roads of the day and using other such evidence, they then were able to deduce where exactly the original Rubicon had been and which river today was once the Rubicon (the Fiumicino river today is about 1 mile away from where the Rubicon used to flow around that crossing site).

Expand for References| Share the Knowledge! |

|