Working for Figurative Peanuts and Literal Beer, the Fascinating Story of Jack the Signal”man”

For most people, saying “a monkey could do my job” is a roundabout way of saying that their current position of employment isn’t exactly that mentally taxing. For James Wide though, it was more of a statement of fact because for 9 years in the late 19th century, his job of railroad signalman at Uitenhage station in South Africa was literally done by a chacma baboon called Jack.

For most people, saying “a monkey could do my job” is a roundabout way of saying that their current position of employment isn’t exactly that mentally taxing. For James Wide though, it was more of a statement of fact because for 9 years in the late 19th century, his job of railroad signalman at Uitenhage station in South Africa was literally done by a chacma baboon called Jack.

Jack came to prominence thanks to a tragic event in 1877 when his eventual owner, James Wide, lost both of his legs in a horrific accident. Prior to the accident, Wide had worked for Cape Government Railways as a guard. During his tenure as a railway guard, Wide developed a knack for jumping between and onto moving trains, which earned him the wholly unimaginative nickname, “Jumper”.

If you’re thinking that Wide’s habit of jumping between moving trains had something to do with him eventually losing both of his legs, you’re absolutely correct. After mis-timing a jump between two trains, Wide landed on the tracks and was unable to move in time to stop the 80 ton car from crushing his shins and feet. The damage was so extensive that Wide’s legs had to be amputated at the knees, leaving him crippled and of little use to the company.

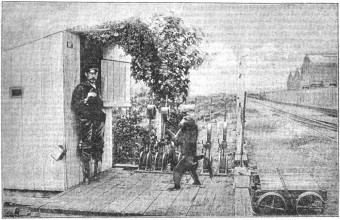

Not to be dissuaded, after recovering from his injuries, Wide carved himself a pair of peg legs and begged his superiors at the railway company to give him a job. Wide’s pleas didn’t fall on deaf ears and he was given the job of signalman, which basically put him in charge of conveying information to conductors via the various signals placed on the tracks, among other similar duties. Although the job required little physically strenuous activity, since all of the signals were controlled by a series of levers that Wide could reach from a chair, he still had troubled getting to and from work. To help with this, the ever industrious Wide made himself a trolley that he could sit on.

Even with the trolley, getting to work was still a hugely tiring endeavour for Wide and for a while, he struggled with this task until, according to a July of 1890 edition of the science journal, Nature, Wide spotted the fuzzy solution to all of his problems- a baboon leading an oxen cart at his local market in 1881. A curious Wide struck up a conversation with the animal’s owner and learned that along with being trained to obey a few simple commands, the baboon, who was called “Jack”, was sufficiently strong enough to push and pull relatively heavy loads.

Upon learning this, Wide asked the owner if he’d be willing to part with the animal so that he could train it to push him to and from work. The owner, perhaps moved by Wide’s condition or maybe Wide just offered a price he couldn’t refuse, for whatever reason agreed to give up ownership of Jack. Again according to Nature, before the two men parted ways, the owner explained to Wide that he should give Jack a “tot of good Cape brandy” every night if he wanted him to work, as without it, the baboon would spend the next day sulking and would even become disobedient. (This is similar to the famous circus elephant, Jumbo, who would reportedly get very annoyed if his trainer forgot to give him a bottle of beer before he went to sleep).

Upon learning this, Wide asked the owner if he’d be willing to part with the animal so that he could train it to push him to and from work. The owner, perhaps moved by Wide’s condition or maybe Wide just offered a price he couldn’t refuse, for whatever reason agreed to give up ownership of Jack. Again according to Nature, before the two men parted ways, the owner explained to Wide that he should give Jack a “tot of good Cape brandy” every night if he wanted him to work, as without it, the baboon would spend the next day sulking and would even become disobedient. (This is similar to the famous circus elephant, Jumbo, who would reportedly get very annoyed if his trainer forgot to give him a bottle of beer before he went to sleep).

Initially Wide simply trained Jack to push his trolley (which had been designed by Wide to fit on train tracks) along the half mile section of track between his house and the signal box he worked in. It wasn’t long though before Wide realised that Jack was a lot smarter than he’d assumed and could be trained for other tasks. For example, one of Wide’s duties involved grabbing a key to the coal store from a locked box and delivering it to train drivers when they tooted their whistles four times. After only a few days of working together, Jack picked up on this and soon began grabbing the key before Wide could whenever he heard the appropriate number of whistles and delivered it himself.

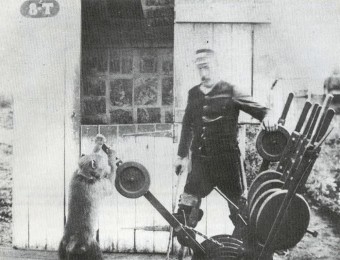

With a bit of training, Jack also learned to operate the levers in the signal box that controlled which section of track a train would travel on as it passed by, similarly picking up on the audio cues given by drivers. While the system itself wasn’t that complicated, consisting of a few levers that controlled certain pieces of track that would be pulled in a certain order based on whether a driver tooted one, two or three times, and is something you could probably train a dog to do with the right setup, Jack had something dogs don’t have- opposable thumbs, which made him a bit more useful with the equipment at hand.

With a bit of training, Jack also learned to operate the levers in the signal box that controlled which section of track a train would travel on as it passed by, similarly picking up on the audio cues given by drivers. While the system itself wasn’t that complicated, consisting of a few levers that controlled certain pieces of track that would be pulled in a certain order based on whether a driver tooted one, two or three times, and is something you could probably train a dog to do with the right setup, Jack had something dogs don’t have- opposable thumbs, which made him a bit more useful with the equipment at hand.

Jack soon became a familiar figure at the signal hut and drivers didn’t take long to become accustomed to the unusual sight of a disabled man and a baboon working in tandem whenever they passed through Uitenhage station. As you can imagine though, some passengers weren’t exactly enthused with the idea of their lives literally being in the hands of a baboon, and after one particular member of the public caught sight of Jack in the signal hut, a complaint was filed and the pair were unceremoniously fired.

Wide appealed to the company to reconsider their decision, arguing that Jack actually knew what he was doing. After several more workers stepped forward to argue that, in their experience, Jack was doing a pretty decent job prior to being fired , the company begrudgingly agreed to give the baboon a test.

Wanting to make sure Jack could handle even the most complicated of scenarios, the test was structured such that they played a series of rapidly changing whistles at Jack after placing him in front of a set of levers with the same layout as those in the signal hut. Jack passed this test without making a single mistake and he and Wide were given their jobs back.

Since Jack was now an official employee of the company, instead of just a pet Wide brought to work, Nature reported he was given a salary of 20 cents per day (about $5 today), daily rations and a beer on Saturdays.

Hiring Jack proved to be a smart move for the company since not only did they get a tourist attraction that brought people from all over to ride their trains to see the baboon, but they also got a fiercely loyal guard with imposing baboon arms to chase away vandals and trespassers. Besides signal operator and occasional guard, during his time with the company, Jack was also reportedly trained to clean, move railway sleepers, garden and was officially put in charge of the keys to the coal yard.

Unfortunately, Jack met and untimely end when he contracted and died from consumption in 1890 (see: Why Tuberculosis was Called Consumption), which interestingly enough “Old World” monkeys like Jack are highly susceptible to, unlike “New World” monkeys. In total, Jack worked for the railway company for about nine years before his death.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Monkey Artist Hoax

- The Horse that Could Do Math: The Unintentional Clever Hans Hoax

- Do Elephants Really Have Great Memories?

- The Exceptional Memories of Goldfish or Why You Should Never Put a Goldfish in a Simple Fish Bowl

- The Origin of the Green, Yellow, and Red Color Scheme for Traffic Lights

Bonus Facts:

- As mentioned, Jack’s story was initially widely covered in an 1890 edition of the science journal, Nature. From there, it remained a fairly obscure tale until it was covered again a century later by The Telegraph Newspaper. After the Telegraph covered it, initially, many assumed to the story to be a hoax, or at least wildly exaggerated. However, along with the article from Nature, surviving anecdotal evidence, and pictures and newspaper clippings from the time, Jack’s existence and role with the railway was also corroborated by still existing correspondence between scientists who encountered him from the era. Today his skull can reportedly be found at the Albany Museum in Grahamstown South Africa.

- The most visible difference between apes and monkeys is that (usually) monkeys have tails whereas apes do not. Apes are also often regarded as being smarter and physically larger than monkeys, though as with the tail rule, this isn’t always the case.

- At Yale-New Haven hospital, economist Keith Chen and psychologist Laurie Stanos taught capuchin monkeys to use money. Among other fascinating results from this study was an interesting incident where one monkey managed to steal an entire tray of money tokens and flung them into the main cage that housed all the monkeys before it could be caught. The monkeys then all scrambled for the coins. With the temporary surplus of money, allowing for expenditures beyond food, and the fact that the monkeys had no concept of saving, funny enough, one of the monkeys was observed paying another monkey for sex. Since that exchange, steps were taken to assure the monkeys would no longer be able to pay one another for sexual acts.

Jack isn’t the only animal in relatively recent history employed by a railway. For example, in the Japanese town of Kinokawa the “station master” for Kishi Station is a female calico cat called Tama. Tama was a stray that lived near the station and was regularly fed by an employee there. When the station became automated in 2007 to cut costs, Tama was “hired” and given food instead of a salary so that she wouldn’t starve. News of Tama’s hiring quickly spread and the station saw an increase in traffic as people travelled to the station just to see her. Tama is tasked with greeting passengers and even wears a tiny station master hat while working.

Jack isn’t the only animal in relatively recent history employed by a railway. For example, in the Japanese town of Kinokawa the “station master” for Kishi Station is a female calico cat called Tama. Tama was a stray that lived near the station and was regularly fed by an employee there. When the station became automated in 2007 to cut costs, Tama was “hired” and given food instead of a salary so that she wouldn’t starve. News of Tama’s hiring quickly spread and the station saw an increase in traffic as people travelled to the station just to see her. Tama is tasked with greeting passengers and even wears a tiny station master hat while working.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Great story. If ind it interesting that with ONE LETTER they were fired. Just like the inolerance we have today. What we DON’T have today is the fact they went back and gave him a chance to prove himself rehired him and in essence told that one person to FO.

I’ve never seen a good source for this, other than the owner’s own story. Every other article is based on that one, so it’s only that guy’s word. It’s always smacked of being extremely embellished to me.

Interesting story. By any chance, do you have the name of the article and particular edition/citation for that July 1890 article in the journal, Nature? (I searched for it, but more information is needed) Also, do you have any further information about Wide’s wishes for the interment of his beloved Jack? Many thanks!

I visited the Albany museum in Grahamstown yesterday and found a display of “Jack’s skull” and a write-up of his story! Apparently his hide was also sent to be displayed, but was returned due to it being in bad condition. Fake, very embellished or true, it is a fascinating story nonetheless!