Toads Around Your Neck and Forcing Kids to Smoke- Escaping The Great Plague of London (1665-1666)

Occurring between 1665 and 1666, the Great Plague wasn’t exactly the first time London had experienced such a terrifying spread of disease, with periodic cases being reported in the city for decades up to this point and, of course, that time about two-thirds of China’s population and then a decade later about half of Europe’s, including an awful lot of people from jolly old England, up and died during the “Black Death”. Nevertheless, the Great Plague was certainly noteworthy. According to the Bills of Mortality from the year, in 1665 alone 68,596 deaths occurred in London as a result of the plague. However, it is generally thought that this number is drastically under-recorded as the likes of groups like Quakers did not report their death tolls and many poor were simply dumped in mass graves without their deaths being recorded.

Occurring between 1665 and 1666, the Great Plague wasn’t exactly the first time London had experienced such a terrifying spread of disease, with periodic cases being reported in the city for decades up to this point and, of course, that time about two-thirds of China’s population and then a decade later about half of Europe’s, including an awful lot of people from jolly old England, up and died during the “Black Death”. Nevertheless, the Great Plague was certainly noteworthy. According to the Bills of Mortality from the year, in 1665 alone 68,596 deaths occurred in London as a result of the plague. However, it is generally thought that this number is drastically under-recorded as the likes of groups like Quakers did not report their death tolls and many poor were simply dumped in mass graves without their deaths being recorded.

This latter point is particularly significant as many of the more affluent city members left London when the plague broke out, including King Charles II and his entourage who left the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Lawrence, to deal with the plague while the king and court retired to Salisbury; they possibly brought the plague with them in the process, as it broke out there after they arrived. Once this happened, the king and court retired to Oxford to wait it all out.

In the end, somewhere between 25%-50% of the population of London died as a result of the plague during 1665-1666. With everyone dropping like flies and nobody knowing what was causing the plague in the first place, this lead to some interesting methods of preventing its spreading, as we’ll get to in a moment.

So how did it all start? Well, this was one of the many waves of the bubonic plague that had been literally plaguing much of the developed world for a few centuries up to this point off and on. We now know that the plague was generally transmitted via fleas that carried strains of Yersinia pestis microbes they had picked up via rats. As for this specific iteration of the plague around London, the first recorded instance was just outside of the city in a parish known as “St Giles-in-the-Fields” sometime early in the spring of 1665. Soon after this, the number of reported cases and the death toll rapidly increased until it reached its peak in the summer of the same year, during which thousands of Londoners were dying each week.

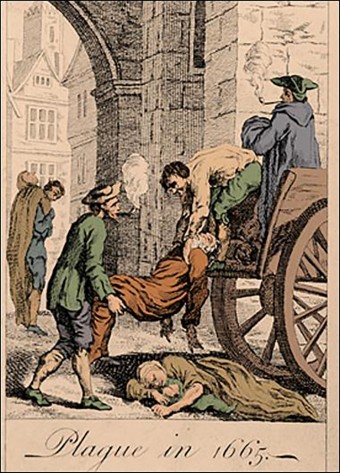

In fact, the death rates became so severe that daytime collection of bodies was banned as those in charge feared a mass-panic if people were to see the massive amount of bodies being carted off by dead-cart drivers and dumped into mass graves every day. (One such mass-grave was found to house 1,114 bodies, being dug down until the grave diggers hit the water table at about 25 feet.)

However, this daytime ban didn’t work out at all because there were simply too few dead-cart operators to keep up with carting away all the bodies just at night. As a result, it was common for people to stack the bodies in the streets, rather than wait for a dead-cart driver who had room on his cart. With rotting corpses literally piling up, the ban on daytime collection was lifted.

As you can imagine from all this, fear ran rampant and terrified Londoners tried anything and everything possible to ward off the disease. As mentioned, since the actual cause of the plague was still a mystery at this point, many of these preventative measures were either useless or harmful in of themselves. For instance, it was a common idea back then that the plague was caused or at least facilitated by “bad air”. As a result, besides bonfires being kept burning throughout the city at all times by order of the authorities and homes also having their fires going day and night, regardless of outside temperature, many took to smoking tobacco as a way of keeping the air going into their lungs free of disease.

This led to a rather surreal situation in which people of all ages, including children, were essentially forced to smoke (or start smoking if they hadn’t previously). For instance, AJ Bell wrote a few decades after the plague,

For personal disinfections nothing enjoyed such favour as tobacco; the belief in it was widespread, and even children were made to light up a reaf in pipes. Thomas Hearnes remembers one Tom Rogers telling him that when he was a scholar at Eton in the year that the great plague raged, all the boys smoked in school by order, and that he was never whipped so much in his life as he was one morning for not smoking. It was long afterwards a tradition that none who kept a tobacconist shop in London had the plague.

(If you think that’s weird, how about the time when people commonly blew smoke up a person’s arse to save them from drowning, including equipment for the procedure hung along major waterways like the River Thames, much like AEDs are today.) Other more sensible preventative measures included cleaning money in vinegar before handing it to a shopkeeper, not letting those same shopkeepers touch raw food with their bare hands and wearing dead toads around your neck… (Not to keep being linky, but there was also a time when putting frogs in milk was used as a way to preserve it, sans refrigeration. Be glad you live in the 21st century!)

Another thing that Londoners believed helped spread the plague was the many stray cats and dogs that roamed London’s streets; so much so that an official edict from King Charles II stated that “no Swine, Dogs, Cats or tame Pigeons be permitted to pass up and down in

Streets, or from house to house, in places Infected.” As a result, many thousands of these animals were killed and promptly buried or burned. While in some sense they weren’t exactly wrong on this one (the dogs and cats carried fleas that may or may not have been previously infected with the offending microbes), this nonetheless is generally thought to have had a net effect of helping the plague’s staying power as the stray cats and dogs formerly helped keep the more worrisome rat population somewhat in check.

Perhaps the most extreme thing Londoners did back then to help curb the spread of the disease was quarantine any house that had been host to a plague victim by sealing it shut for 40 days. The doors to these houses would be locked and then marked with a huge red cross, above which the words “Lord have mercy upon us” would be scrawled. To ensure that nobody escaped, a guard would also often be posted outside.

Since it was common to seal a house with all of the occupants still inside, regardless of whether they were sick, many Londoners took to bribing the guards tasked with searching homes for signs of the plague to ignore any such signs in their home, which is one of the reasons records from that era are so lax. When this didn’t work, some resorted to fleeing their homes and all their possessions before their house could be sealed, choosing to risk living on the street rather than succumb to plague or starve to death locked away.

Even when a house was bolted shut and placed under the watch of a burly guard, there were still a number of escape options available to an enterprising occupant. One of the more popular and straightforward escape methods was to simply convince the guard to temporarily leave his post, usually via a bribe. Some of the more clandestine escape methods from the time included tunnelling to freedom, enlisting the help of friends to poison or drug the guards and stealthily making a daring rooftop escape at night like a plague-ridden ninja.

Other, less subtle, methods of escape included punching through the thinnest walls of the property to the outside world or setting fire to the building and escaping in the confusion. In at least one case, a man used a makeshift explosive crafted from fireworks to blow up his front door as he and his entire family leapt from a first story window to escape at the same time. It turns out, going out the window wasn’t necessary though. The blast had killed the guard.

Arguably the most ingenious method of escape was to, essentially, go fishing for guards. In this method, the occupants of the home would carefully lower a noose from windows to settle around the necks of the guards outside their homes and either drag them upwards to their death, or just choke them until they surrendered their keys. In the event of the former, the guard’s body would then be discretely disposed of by wrapping it in a sheet (thereby disguising it as the body of a plague victim which nobody would check very closely) and dumping it unceremoniously into a passing dead-cart. Amazingly, it’s noted that at least “a score” of guards (about 20 to you and me) were killed in this way by desperate citizens.

Luckily for both citizens and guards, the worst of the plague passed by the fall of 1666 and absolutely nothing terrible happened to London ever again… Unless you want to count the huge fire that tore through the city just a year later, destroying approximately 85% of the walled area of the city, leaving about 65,000 people homeless, and destroying an awful lot of records concerning the recent plague, making it difficult to nail down things like the exact death toll and how many people were infected but ultimately recovered. Then, of course, there were all the other times horrible things happened in London throughout its very eventful history. But who’s counting?

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The “Forgotten Plague”, Dance Mania

- Why Native Americans Didn’t Wipe Out Europeans With Diseases

- Warding Off Diseases: The Fascinating Origin of the Word “Abracadabra”

- How Did They Settle on Six Feet Deep for Graves?

- Why We Say Gesundheit When Someone Sneezes

Bonus Facts:

- During the time of the plague, the city of London would publish weekly statistics describing the number of people who’d died that week and from what cause. As you’d expect, “plague” was generally the number one cause between 1665 and 1666, however, a less noted but infinitely more interesting cause listed during this time was “Frighted”. This was used to describe those who’d supposedly died from the sheer fright or shock of being told they’d been diagnosed with the plague. Other interesting or quirky causes of death noted in these “Bills of Mortality” include: people dying of “grief”, “sore legges”, a surprising number from “Teeth”, and, of course, the age old cause of death- “griping in the guts”.

- Doctors tasked with looking after plague victims were required by law to carry with them a “white stick” at all times so that people knew they’d been near plague victims and to avoid them.

- At the peak of the plague, trade with London was largely cut off. As a result, food could only really be purchased by literally yelling at merchants from the walls of London who’d then leave the food near the walls in return for an agreed upon amount of money that had to be left in either water or vinegar to clean it.

- While this iteration of the plague was largely confined to London, it did spread to other parts of England, most notably the small village of Eyam which famously quarantined itself so that nobody else nearby could become infected (which did, in fact, work). However, this quarantine resulted in a higher death toll than London, with approximately 80% of the population of the village dying as a result of the plague.

- To leave or enter London during the plague’s peak, one needed a “certificate of health” from a doctor. This, of course, led to a massive counterfeit trade in these items and numerous examples of unscrupulous doctors taking bribes in return for literal clean bills of health.

- As for why houses were quarantined for exactly 40 days, according to Judeo-Christian tradition, that was the amount of time required for a “ritual purification” of a given area. Hippocrates himself was also known to believe that the 40th day of an illness was the most important and that if a person survived that, they’d generally be okay. The word “quarantine” itself comes from Italian “quaranta giorni” which means “40 days”. This was also the amount of time ships would be required to stay at sea before making port during the time of the aforementioned Black Death to ensure no sick were on board.

- The Plague and the Fire

- The London Plague of 1665

- Museum of London: London plagues 1348–1665

- 17th Century: Plague

- Daily Life During the Black Death

- The Black Death and early public health measures

- National Archives: Great Plague of 1665-1666

- Encyclopedia of the Black Death

- The Great Plague of London

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

GREAT WORK ON THAT PLAGUE. WAS A FASCINATING MORBID READ. AS ALWAYS, EXCELLENT. TNX KARL

You’re right, I’m so glad I didn’t live back then! This and the sewer one, omg, bleeech and gag :/ Those poor people 🙁