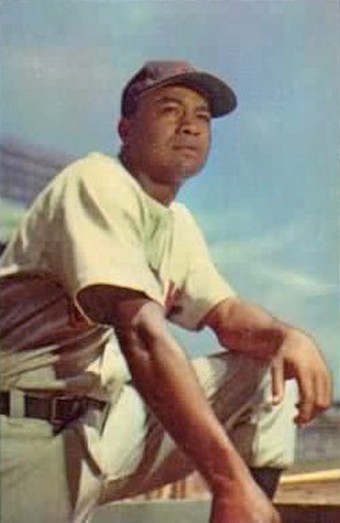

The Forgotten Hero: Larry Doby

On April 15, 1947 in Brooklyn, New York, the great Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier and became the first African-American in 67 years to play in the Major Leagues. (Yes, Robinson was not the first, as is often stated.) Less than three months later, on July 5, 1947 in Cleveland, Ohio, Larry Doby became the second African-American ball player break the color barrier, and the first on an American League team. Although history tends to forget Doby’s much-less hyped debut and subsequent stellar performance, his life, career, and path to the majors were just as interesting and courageous as Robinson’s. As Dave Anderson wrote in a 1987 New York Times article, “In glorifying those who are first, the second is often forgotten … Larry Doby integrated all those American League ball parks where Jackie Robinson never appeared. And he did it with class and clout.”

Records point to Larry Doby being the grandson of Burrell Doby, a South Carolina native who was born into slavery in 1852. There are few other records (if any at all) of Burrell Doby until the US Census of 1880, where he appears as a freeman and a sharecropper in a town near Camden. It was around this time when he and his wife gave birth to David Doby, Larry’s father. Through David’s childhood, the Dobys were one of the more successful black families in the region. As a teen, David worked as a stable hand and later joined the Army to fight in World War I, serving for five months before being honorably discharged.

After the war, David again groomed horses, but in his free time he took up another hobby – playing baseball. He was good too, playing semi-pro ball and according to Richard DuBose who was involved in black baseball for over a half century, David was “the greatest hitter I ever saw.” David met Etta Brooks, his soon-to-be-wife and mother to Larry, through baseball as well. David, walking through town, spotted Etta smacking a long home run in a game on the street in front of her parents’ house. It seemed Larry got the baseball genes from his parents.

Lawrence “Larry” Doby was born on December 13, 1923 in Camden, South Carolina at Etta’s mother’s (known as “Miss ‘gusta”) house. Given the nickname “Bubba,” Larry lived with his grandmother when his parents separated. He still saw both parents, but that changed when “Bubba” was eight. In 1931, David Doby drowned when he fell out of his fishing boat. The rough few years continued when “Bubba” was forced to move in with an Aunt and Uncle when Miss ‘gusta fell ill. He eventually moved with his mother to Paterson, New Jersey where he began to excel at sports.

At Paterson Eastside High, Larry (shedding his childhood nickname) was a three-sport star in football, basketball, and baseball. At his school, there were only a few African-American students and he had just one as a teammate (in basketball). While in high school, Doby was known as a hard-worker, mild-mannered, and quiet. He was also a star, helping the school win multiple state championships, including one in football (Larry played wide receiver). Upon winning, the team was invited to play a game in Florida, but the tournament hosts told them that Larry could not play due to the color of his skin. The team, in a show of support, refused to play the match.

During the summers, Larry played semi-pro baseball and basketball, thriving in the former (he was an unpaid substitute in basketball for the Harlem Renaissance). He graduated and earned an athletic scholarship at Long Island University to play basketball under legendary coach Claire Bee. He never played college baseball because the famed Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues signed him to play for $300 (about $4200 today) in 1942. Attempting to preserve his amateur status and keep his future options open, he played under a fake name, “Larry Walker.”

With the country at war, Larry joined the US Navy in 1943 and was assigned to be a physical education instructor. He bounced around stateside, before being sent overseas to the Pacific Island of Ulithi. He loved baseball, but saw more of a financially secure future as a teacher or coach so planned to pursue that after the war. However, when in October of 1945 Jackie Robinson signed a contract with the Montreal Royals of the International League, it became more plausible that Larry could earn good money – major league money – playing pro ball. Said Larry years later, “Growing up in a segregated society, you couldn’t have thought that that was the way it was gonna be. There was no bright spot as far as looking at baseball until Mr. Robinson got the opportunity to play in Montreal in ’46.”

He was honorably discharged from the Navy in January of 1946 and went back to play for the Newark Eagles. There, he was again the star, along with future Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, on the team that won the Negro League World Series. Doby could hit, field, and run. Plus, at only 23, he was young – a good six years younger than Jackie Robinson. It was no surprise to anyone that he was the top candidate to be the second African-American in that era to get a shot at the Majors.

Major League Baseball was ready for change, especially since former baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis had died in 1944. Mean, bullying, and unabashedly racist (not to mention sexist, banning 17 year old Virnett Beatrice “Jackie” Mitchell from the Major and Minor Leagues, voiding her contract in the process, after she struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig back to back on just six total pitches), Landis was a most ardent opponent to integration. And as commissioner, he was the boss.

So, when he died and Happy Chandler took over as commissioner, things could only get better. Even though Chandler was a Southerner – he was a former Kentucky Senator – he was relatively progressive. Chandler approved Robinson’s contract in 1947 and explained that Robinson’s service to his country in the War was enough for him- “If a black boy could make it on Okinawa and Guadalcanal, he could make it in baseball… I don’t believe in barring Negroes from baseball just because they are Negroes.” Chandler would go on to be the governor of Kentucky in the late 1950s, where he forced the public schools there to integrate.

Bill Veeck, the unique owner of the Cleveland Indians, had proposed integrating baseball in 1942, but was quickly turned down by Landis. After Robinson’s opening day with the Dodgers, Veeck acted quickly. He intensely scouted the Negro Leagues and between Doby’s skill set, temperament, and youth, he knew who he was going to sign. Veeck’s strategy was different than Branch Rickey’s (the man who signed Robinson for the Dodgers), though. He didn’t want Doby to play in the minors, but rather to start right in the majors- no small task. He also insisted on paying for Doby’s rights from the Newark Eagles, ten grand (about $102,000 today), plus an extra five grand when he remained in the majors for a month. Rickey never paid Robinson’s former team a dime. On July 3, 1947, Veek signed Larry Doby to a contract, but allowed him to play one more game with the Newark Eagles (where he hit a home run) before taking a train to Cleveland.

On July 5, 1947, Larry Doby joined his new team and, just like as happened to Robinson, the reception wasn’t great. Several new teammates, including reportedly Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller, turned their back to him and refused to shake hands. Doby stated of meeting his new teammates, “I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return. Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.'”

It wasn’t until second baseman Joe Gordon tossed Doby a ball and asked him to play catch that the tension subsided somewhat and he was allowed to take part in warm-ups. Gordon would go on to be Doby’s best friend on the team for years to come.

Doby didn’t start that game. In fact, he would start only one game all season, but he did get to pinch hit, the first time striking out. His performance that season was not good, no doubt hurt by lack of playing time (only given 33 plate appearances), being asked to play a new position he’d never played before, being put directly in the Majors, and of course all the while with death threats reigning down. He was also somewhat segregated from his teammates, generally not even allowed to stay at the same hotel as the team. In the end, he batted just .156 with a .182 on base percentage and a .188 slugging in his extremely limited playing time.

Despite calls from the media and some in the community for Doby to be removed from the team, both he and Veek paid little attention. That season Jackie Robinson and Doby also frequently spoke on the telephone to help keep each others’ spirits up.

When the season ended, Doby found other ways to spend his time than listen to criticism – he played basketball. He signed a contract with his hometown team, the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League. He was the first African-American player in the league and possibly the first in all of professional basketball.

There was some question going into the 1948 baseball season as to whether Doby should even make the team, given his poor performance the season before, but he quickly silenced the doubters, reportedly even hitting close to a 500 foot home run during spring training. Once the season started, and with a lot more playing time (121 games and 500 plate appearances), Doby showed exactly what he could do, batting .301, with a .384 on base percentage and 14 home runs, all while reportedly playing an outstanding center field. With this performance, he helped the Cleveland Indians win 97 games, as well as earn a chance to play for the championship in the World Series against the Boston Braves.

In the Series, with the Indians up two games to one, Doby belted a third inning home run that made the score 2-1 Indians. The score would hold and the Indians would win, taking a three game to one series lead. After the game, a photo was published in newspapers across the country of Larry Doby joyfully embraced by the starting pitcher of the game and white teammate, Steve Gromek. It has since become famous. To many, the picture represented acceptance, racial tolerance, and the spirit of friendship. To Doby, that embrace meant so much more, “That was feeling from within, the human side of two people, one black and one white. That made up for everything. I would always relate back to that whenever I was insulted or rejected from hotels. I would always think about that picture. It would take away all the negatives.”

After the season was over, a parade was thrown in Paterson in Doby’s honor. Shortly thereafter, he attempted to use the extra earnings from the post-season to buy a house in a white neighborhood in Paterson, but was denied thanks to a petition from certain members of the community that had so recently thrown him a parade. In the end, it took intervention from Paterson’s mayor before he was able to buy a house there.

As good as he was in 1948, Doby would be even better in 1949, earning all-star honors while belting 24 home runs and hitting .280 with a .384 on base percentage. The next season he topped that by a good margin hitting 25 home runs with a .326 batting average and a .442 on base percentage. He would become an all-star seven times, hitting 253 home runs over his impressive injury shortened 13 year career (ultimately being forced to bow out after nagging injuries, and eventually an X-ray revealing significant bone deterioration in his ankle).

But Doby’s accolades didn’t end with his playing career, or with baseball, for that matter. In 1978, Bill Veeck hired him to manage the Chicago White Sox. Doby once again came in second- baseball’s second African-American manager (Hall of Famer Frank Robinson was the first when he managed the Indians with Doby as the first base coach.) In 1980, NBA’s New Jersey Nets hired Doby to be their director of communications, a post he would remain in until 1989. Nine years later, Doby was finally elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Larry Doby died of cancer on June 18, 2003. Upon Doby’s death, former MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent perhaps said it best when he stated,

Larry’s role in history was recognized slowly and belatedly. Jackie Robinson, who broke the color line first but in the same year, quite naturally received most of the attention. Larry played out his career with dignity and then slid gracefully into various front-office positions in basketball and… baseball. Only in the 90’s did baseball wake up to the obvious fact that Larry was every bit as deserving of recognition as Jackie.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Little Person Who Played in the Major Leagues

- The First Person to Play for Both Baseball’s National League and American League All-Star Teams was a Woman: Lizzie “The Queen of Baseball” Murphy

- From Attempted Suicide to MLB Superstar-The Life and Very Complicated Times of Ken Griffey Jr.

- Why “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” is Sung During the 7th Inning Stretch of Major League Baseball Games

- 20 Interesting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Facts

| Share the Knowledge! |

|