The Largely Forgotten Los Angeles’ Chinese Massacre

On a cool October night in 1871, 18 Chinese men and boys were massacred by a bloodthirsty mob in Los Angeles.

On a cool October night in 1871, 18 Chinese men and boys were massacred by a bloodthirsty mob in Los Angeles.

The Cause

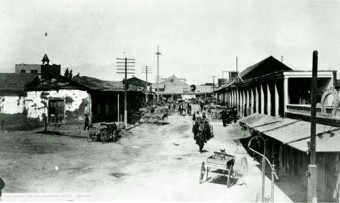

Debate continues over the actual trigger for the riot, but most commentators point to a fight between rival Chinese gangs in Los Angeles’ then-Chinatown on Calle de los Negros (today part of Los Angeles Street).

According to reports, on October 24, 1871:

The difficulty arose from a quarrel . . . [where both gangs] claimed a moon-eyed beauty, lately imported from the Celestial Empire, and from angry words the two finally came to blows. The disorder naturally called the police officers to the scene, and after much parleying and an attempted arrest [the gangs] finally fired at the officers, wounding both seriously.

The Massacre

One of those injured, Robert Thompson, may not have been a police officer, and has variously been described as a saloon owner and rancher. Regardless of his profession, he died, and about 5:30 p.m., all hell broke loose.

Since racial tensions, particularly against the Chinese, had been simmering for years, this act of civil disobedience lit a fire of hatred: “The motley Mexican, American and European population . . . [was] aroused [and] in a few minutes a large crowd gathered on the streets and in the wildest rage rushed upon Chinatown.”

The crowd of rioters began lynching innocent people, arbitrarily chosen, although apparently, they weren’t very skilled at it: “[At] the corner of Temple and New High streets . . . a rope was hastily put around his neck and he was summarily hauled up. The rope broke and . . . he was again hung up; this time successfully.”

Trying to protect themselves, many Chinese sought shelter and barricaded the entrance to a building. The rioters set this on fire, driving the occupants out into the mob, which: “Utilized all the posts and sheds in the vicinity to hang their victims upon, and spared neither old nor young.”

Nor did they spare the well-liked: “One of the victims was a Chinese doctor, an inoffensive man, respected by all the white people who knew him. He pleaded in English and in Spanish, for his life, offering his captors all his wealth . . . but in spite of his entreaties he was hanged; then his money was stolen, and one of his fingers cut off, to obtain the rings he wore. The doctor’s name was Gene Tung…”[i]

Women and children also aided in the massacre, and many rioters looted the dwellings of the poor, and now devastated, Chinese.

The riot ended at about 9:30 p.m. when Los Angeles County Sheriff James Burns raised a group of 25 “good and law-abiding citizens to follow him to Chinatown.”[ii] By some accounts, when they arrived the fighting had already ceased.

At the end of the mayhem,18 people were dead, including at least 10 by hanging and four by gunshot.

Trial and Conviction

Several criminal and civil trials were held, and eight people were found guilty of manslaughter for the killing of Dr. Tung (Tong). They were Esteban Alvarado, Charles Austin, Refugio Botello, L.F. Crenshaw, A.R. Johnson, Jesus Martinez, Patrick M. McDonald and Louis Mendel, and each of these, except Mr. Botello, was imprisoned by the end of 1872.

Overturned on a Technicality

Some commentators believe the prosecution’s heart wasn’t in trying the rioters, and the ultimate outcome may help prove this point.

On appeal to the California Supreme Court, it was discovered that the prosecutor, who tried each of the convicted killers for the murder of Dr. Tong, “had failed to introduce evidence that Tong had been killed,” or for that matter, even place that allegation in the indictment.[iii]

Since a conviction for manslaughter requires a killing, and given that there was no evidence of a killing in the record, each of the rioters’ convictions were set aside. Memorialized in the opinion, People v. Crenshaw, issued on May 21, 1873, this decision has been widely criticized as: “A two-paragraph opinion that cited no statutes or judicial precedent, they summarily decided that they were not able to reach the legal conclusion from the language of the indictment that any person was actually murdered.”[iv]

No subsequent trials were conducted, and no one has ever been held to account for the 18 murders. At the time, the Los Angeles Star commented, “To this ‘most lame and impotent conclusion’ has come the great Chinese riots.”[v]

Conspiracy theorists have argued that the lackadaisical prosecution was part of a plan by the town’s leaders to downplay the city’s troubles and improve its public relations, as well as hide the fact that many of its leading citizens were cheering the rioters on as the crowd lynched the innocent men and boys.

In support of this theory, some point to the fact that many of the key actors involved in the massacre died by violence within a few years of it. One of the Chinese gang leaders was “hacked to death by an assassin,” and one of the defendants was “accidentally” shot when a rifle “fell” and the gun discharged into his chest (when he was alone with one of the police officers who was present at the riot).

That officer later died in an explosion while working as a railroad detective, and a prominent member of the community who had allegedly cheered the lynching was “mistook [by] his friend for a deer” and accidentally shot twice!

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Can the Great Wall of China Really Be Seen from Space?

- Why Do Asian Nations Use Chopsticks?

- An Encyclopedia Finished in 1408 That Contained Nearly One Million Pages

- Origin of the “Chinese” Fire Drill

- Was There Really a General Tso?

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

For a long while Calle de los Negros was known by the pejorative “N***** Alley” and people who didn’t know the history or that it referred to the Chinese. A similar name change is true about a location on the river near Sacramento that is now called Negro Bar but was originally camp location of African American miners. http://www.folsomhistorymuseum.org/1mining_towns.htm

Second paragraph of “The Massacre” says “this act of civil disobedience lit a fire of hatred” not sure two gangs clashing and then shooting and killing people counts as “civil disobedience”. Not that the other side was civil either.

Tragic and pointless all around.