The Colfax Massacre of 1873

In the early days of the United States, cotton and tobacco crops on the east coast are remembered as big contributors to the ongoing slave trade. Meanwhile, the sugar cane plantations in Louisiana are often forgotten. Because of the back-breaking work of maintaining the sugar cane crops, white settlers started importing African slaves to do the work for them. It resulted in a roaring slave trade that saw around 330,000 slaves residing in the state in the lead-up to the Civil War—a number nearly equal to that of the 370,000 or so free citizens.

In the early days of the United States, cotton and tobacco crops on the east coast are remembered as big contributors to the ongoing slave trade. Meanwhile, the sugar cane plantations in Louisiana are often forgotten. Because of the back-breaking work of maintaining the sugar cane crops, white settlers started importing African slaves to do the work for them. It resulted in a roaring slave trade that saw around 330,000 slaves residing in the state in the lead-up to the Civil War—a number nearly equal to that of the 370,000 or so free citizens.

As you can imagine, when the Union occupied Louisiana toward the end of the war and went about freeing the slaves, it wasn’t met with applause from the plantation owners. Race remained a big issue in the state, as it did elsewhere, for decades following the war. Tensions were high, resulting in numerous outbreaks of violence.

After the war ended, the Southern Democrats who had enjoyed a great deal of power in the government found they were suddenly relatively powerless. Northern Republicans had set up camp on Capitol Hill and placed soldiers in Southern cities to try to maintain peace and order. However, they battled the uprising of white supremacist groups—notably the Ku Klux Klan—who were determined to establish white power in areas with a heavy black population.

Furthermore, the Republicans had passed a series of amendments that made black people equal citizens with whites. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the constitution declared that blacks were free, no one was to deprive them of their constitutional rights, and gave them the power to vote.

It was this last one that particularly frightened the Democrats. As they largely didn’t agree with giving their former slaves any rights, they feared that the newly established African-Americans would use their votes in favour of the Republicans, further diminishing the Democrats’ power.

The years before the 1872 election were marked by bloodshed. White Democrats so strongly opposed black suffrage that 1,081 politics-related deaths were recorded between April and November 1868. The victims were mostly black, and most of their lives were taken by Democratic supporters. However, that didn’t stop the Republican state legislature from establishing new parishes in hopes of engendering more Republican support.

One of those parishes was Grant Parish, which has the town of Colfax as its parish seat. In a few years, Colfax boasted 2400 freedmen and 2200 whites. Then-Governor Henry Clay Warmouth appointed a black veteran named William Ward to command a new state militia unit to be based in Grant Parish, likely in an attempt to balance Louisiana politics. Ward was a solid choice—he had served in the Union Army in the latter end of the Civil War. After his appointment, he recruited other freedmen—several of them veterans—to join him.

In 1872, the Republican vs. Democrat issue came to a head when the election resulted in a dual government. Each of the Governor candidates, Democrat John McEnery and Republican William Pitt Kellogg, believed he had won. They both even held inaugural ceremonies. A Republican federal judge declared that Kellogg’s government was the legitimate one, but the Democrats were beyond listening. They started taking over the police stations in New Orleans.

Fearing that the court house in Grant Parish would be overrun, Commander Ward ordered trenches to be dug around the courthouse. The Republican officers remained in the building overnight, and Ward and his men held the place for three weeks. However, on March 28, white Fusionists called for reinforcements to take the court house back from the Republicans. Some gunfire was exchanged, though no harm was done, and peace negotiations began. They came to an abrupt halt when a white man shot a black soldier. Later, armed black men went after a group of whites. With tensions escalating rapidly, black women and children joined the men at the court house for protection.

On April 8, New Orleans’ Daily Picayune newspaper, which was anti-Republican, posted a headline which attracted more riled whites to Colfax: “THE RIOT IN GRANT PARISH. FEARFUL ATROCITIES BY THE NEGROES. NO RESPECT SHOWN TO THE DEAD.”

Ward had already sent a plea for help to Governor Kellogg, but it had been intercepted. Seeing the growing numbers of white rioters, he left Colfax to deliver his request for additional troops in person. He left on April 11 and did not witness the events that followed.

April 13, 1873 was Easter Sunday, and it was also the day that former Confederate army soldier Christopher Columbus Nash decided to lead his small army against the black solders holding the court house. He did, however, give the women and children there half an hour to leave, after which the shooting started. Later, a cannon was also rolled out.

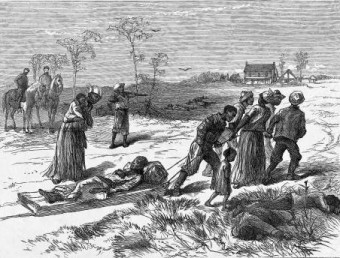

Needless to say, the court house defenders had nothing in their arsenal that could combat a cannon. Many of them fled and were shot on the spot. Afterwards, the remainder surrendered and were taken prisoner. Later that night, the guards got drunk and killed their prisoners. Only one black man, Levi Nelson, survived the carnage—he had been shot, but managed to crawl away from the scene unnoticed.

The exact death toll was difficult to establish as bodies had been dumped in various locations, but at least 105 black people (and some sources cite up to 150) died in the altercation vs. just three of the attacking group.

Unlike many similar events at the time, there were almost some consequences for the attackers. Nine white men in Colfax were charged with murder and conspiracy against the rights of freedmen. Unfortunately, they weren’t found guilty of the crimes due to “vagueness” and were released. The case was appealed, but the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Cruikshank that the federal government could not prosecute in the case of the Colfax killings; that had to be done at the state level, and Louisiana certainly wasn’t going to prosecute white men on behalf of the black population at the time.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court ruling only encouraged white supremacist groups who created additional white-power leagues and continued their reign of terror in the south.

A memorial was erected for the victims decades later in 1950. The memorial simply states:

On this site occurred the Colfax Riot, in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- 20 Interesting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Facts

- The Man Who Personally Executed Over 7000 People in 28 Days, One at a Time

- Jane Elliot and the Blue-Eyed Children Experiment

- Dr. William Brydon, One of the Only Survivors of the Massacre of Elphinstone’s Army That Included Over 16,000 People Killed

- The Rosewood Massacre of 1923

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Wow. Nowadays Republicans are thought of as intolerant and racist. This is the exact opposite of today’s times.