The Olympic Swimmer Who Had Never Been in a Pool Until a Few Months Before Competing in the Olympics

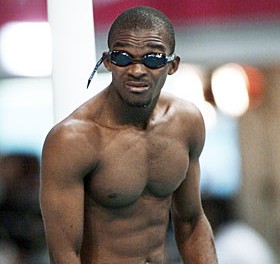

The man was Eric Moussambani Malonga, later nicknamed “Eric the Eel”. Moussambani is from Equatorial Guinea in Africa and only managed to get into the Olympics at all because of a wildcard drawing system put in place by the International Olympic Committee, designed to try to encourage developing countries to participate in various Olympic events.

The man was Eric Moussambani Malonga, later nicknamed “Eric the Eel”. Moussambani is from Equatorial Guinea in Africa and only managed to get into the Olympics at all because of a wildcard drawing system put in place by the International Olympic Committee, designed to try to encourage developing countries to participate in various Olympic events.

Thanks to this drawing, Equatorial Guinea decided to send a swim team to the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia. They put out an advertisement on the radio a few months before the Games to try to get people to come and tryout for the country’s new national swim team which would be going to the Olympics. Those who wished to tryout were to show up at the Hotel Ureca in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea. At the time, this hotel was the only place in the country that had a swimming pool (only 12 meters long).

Two people showed up, one woman, Paula Barila Bolopa (who was a grocery store cashier at the time), and one man, Eric Moussambani. Because of the lack of competition, the only thing the two had to do to get on the team was to demonstrate that they could in fact swim.

Previous to this, Moussambani didn’t know much about swimming, but contrary to what is often reported, he did know how to swim. Said Moussambani:

The first time I swam in the sea, I was 12 years old and was on vacation in my mother’s village. My first time in a swimming pool was on May 6, 2000 in the Hotel Ureca swimming pool…

They just told me to get my passport and a picture ready so they could send me to the Olympics. They said to me, ‘Keep on training.’ I asked them, ‘With who? I don’t have a trainer.’ They said: ‘Do what you can. Keep training because you are going to the Olympics.’

My preparation was very poor… I was training by myself, in the river and the sea. My country did not have a competition swimming pool, and I was only training at the weekends, for two hours at a time. I didn’t have any experience in crawl, breaststroke, or butterfly. I didn’t know how to swim competitively.

The Olympic Games was something unknown for me. I was just happy that I was going to travel abroad and represent my country. It was new for me. It was very far from Africa.

Just three months after hearing the advertisement and then getting selected to represent his country, Moussambani was on his way to the Olympics. He took a somewhat roundabout flight to Libreville (Gabon), then to Paris, then to Hong Kong, and finally to Sydney, a trip that took nearly three days to complete. Along with accommodations, he had £50 of spending money while at the games and an Equatorial Guinea flag for use in the opening ceremony.

Once at the Olympics, he got his first glimpse of an Olympic size swimming pool,

When I arrived, I just went to the swimming pool to see how it is. I was very surprised, I did not imagine that it would be so big…

My training schedule there was with the American swimmers. I was going to the pool and watching them, how they trained and how they dived because I didn’t have any idea. I copied them. I had to know how to dive, how to move my legs, how to move my hands… I learned everything in Sydney.

What makes Moussambani’s story even more compelling is that he would go on to win his heat in the 100m freestyle, albeit in a pretty unorthodox way. You see, at the time, he was to compete against just two other people in the qualifiers, Karim Bare from Niger and Farkhod Oripov from Tajikistan. Both of these two ended up getting disqualified for false starts, leaving just Moussambani, who at the time thought he had been disqualified, before it was explained to him that his competitors were the ones out and that he’d be swimming the heat alone in front of 17,000 spectators.

In order to qualify for the next round, he needed to beat 1 minute and 10 seconds… He didn’t quite manage that. However, for someone with such limited training and technique, he actually didn’t do too bad at the very beginning, even executing an OK dive and looking pretty fast for the first 10 or 15 seconds or so, then quickly faded. As he said,

The first 50 meters were OK, but in the second 50 meters I got a bit worried and thought I wasn’t going to make it… I felt that [it] was important [to finish] because I was representing my country… I remember that when I was swimming, I could hear the crowd, and that gave me strength to continue and complete the 100 meters, but I was already tired. It was my first time in an Olympic swimming pool.

He finished with a time of 1 minute 52.72 seconds (40.97 seconds at the halfway mark), which was about 43 seconds off the qualifying time. This was, of course, a new Equatorial Guinea swimming record, but also unfortunately was the slowest 100m freestyle swim pace in Olympic history. For his efforts, he was immediately a media darling, with fans and some other athletes loving his story. However, many felt that his being allowed to participate was embarrassing, as he had not a hope in the world of actually winning anything, and it was unfair to athletes in more privileged countries that could swim circles around Moussambani, but who weren’t given a chance to compete because lesser swimmers from developing countries were being included. The International Olympic Committee’s president, Jacques Rogge, was one of those, saying he would work to get rid of the wild card system and stated, “We want to avoid what happened in the swimming in Sydney; the public loved it, but I did not like it.”

Of course, the “father” of the modern Olympic Games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, likely wouldn’t have agreed with this negative sentiment at all, as he wanted all countries to compete in the Games. He also once criticized English rowing competitions for not including working-class athletes. He further developed the Olympic motto (Citius, Altrius, Fortius- Faster, Higher, Stronger) after a portion of a sermon given by Bishop Ethelbert Talbo, which de Coubertin was fond of quoting

The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part, just as the most important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.

Certainly Moussambani exemplifies that sentiment.

If you liked this article and the Bonus Facts below, you might also like:

- The Origin of the Olympic Rings

- The Origin of the Olympic Flame Tradition and the Nazi Origin of the Olympic Torch Relay

- The Official Olympic Salute

- How Much are Olympic Gold Medals Worth?

- Moussambani’s 2000 Olympics Swim [Video]

Bonus Facts:

- Since 2012 Moussambani has been the coach of the Equatorial Guinea swim team, when he’s not working his day job as an IT engineer. They actually have a real, competitive team now comprising 36 swimmers, so the Olympic wild card system paid off in that respect. They also have an Olympic size swimming pool to practice in now.

- Moussambani has gotten a lot better at competitive swimming. By 2004, he got his 100m free style time down to 57 seconds, which would have been good enough for him to qualify in the 2004 Olympics, but a visa mistake ended up costing him a trip to that year’s Games. Some have speculated the visa mishap was intentional in order to stop him from competing. The gist of it was that when he submitted his application, his passport photo was somehow lost by the Malabo officials processing it. Some highly placed government officials in his country had previously expressed anger at how he’d embarrassed their country in 2000 and were not enthusiastic about him going to the Athens games. Whatever the case, due to the loss of the photo, his application was denied.

- Moussambani recently started training again along with coaching and he posted his best swim time in 2012 at the age of 34, having it down to 55 seconds in the 100m freestyle, just under 8 seconds off the current Olympic record. As such, he’s decided to come out of semi-retirement from professional swimming to try out for the 2016 games. “I still have a dream. I want to show people that my times have improved, that we have swimming pools in my country now and that I can now swim a hundred meters.”

- Moussambani’s current training routine for the 2016 Olympics is to wake up at 5am and run for 3 km. He then gets ready for work and spends 8am to 5pm there. On Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday he heads down to the pool where he meets his team and trains from 6pm-10pm.

- The 100m freestyle gold medalist (Pieter Van den Hoogenband) in the 2000 Olympics finished with a time of 48.3 seconds, which was a new world record.

- The current world record for the men’s 100m freestyle (long course: 50m pool) is 46.91 seconds, set by Cesar Cielo of Brazil in the 2009 World Championships in Rome.

- The current Olympic record is 47.05 seconds, set by Eamon Sullivan of Australia in the 2008 games.

- Equatorial Guinea’s other swimmer in the 2000 Olympics, Paula Barilia Bolopa, also struggled to finish her heat, this time in the 50m freestyle, finishing with a time of 1:03.97. While it was a new record for the 50m freestyle for Equatorial Guinea, it was also, like Moussambani’s time, a new slowest time record in Olympic history for the 50m freestyle.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I remember seeing this guy swim in an olympic video after it was all over and thinking “That’s awesome”. He may not have been the best, but he sure gave it his all. The fact that he never gave up and has a significantly better time is even more amazing. Rogge is straight up wrong. Being in the Olympics gave him the Olympic spirit, and he is certainly a credit to his country.